| Research Cycle |

Order Kindle versions of Jamie's books

Order Jamie's books online with Paypal or a credit card

|

|

|

| Vol 11|No4|June |2015 | |

The importance of surprise

|

|

2. Does the research task require

|

|---|

Sherlock Holmes and Nancy Drew would win little attention or audience if the solutions to their mysteries were lying in plain sight. The best research projects will involve a substantial degree of mystery and the clues will not pop out at the students. They must do some digging and figure out what is missing. They must show reliance and resourcefulness as they hunt the information that will ultimately allow them to build a case, take a position or suggest a solution to a problem.

The teacher should only allow projects that require such digging. If the students can go to Google and find everything they need with a single search, it is not a good sign. Wondering if a ship captain like Matthew Flinders was guilty of arrogance, the student can go to Google and type the words "Matthew Flinders arrogant" and find many interesting passages that do not, in themselves, answer the question. The documents will provide conflicting evidence and testimony as well as conflicting viewpoints. There is no answer waiting to be copied and pasted.

|

3. Is the research task somewhat baffling? |

|---|

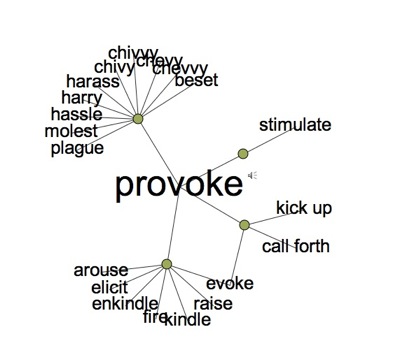

The task should raise the student's eyebrows and cause a frown or two. The thesaurus offers the following words related to baffling - puzzling, bewildering, perplexing, mystifying, bemusing, confusing, unclear; inexplicable, incomprehensible, impenetrable, cryptic, opaque. The important questions in life - such as which treatment or doctor to select for one's cancer - are almost always confounding. There is almost never a simple, satisfying answer readily available. The student must learn to handle this complexity. Note the article "Embracing Complexity." Teachers can encourage students to embrace complexity and manage ambiguity while developing advanced comprehension skills that will help them pierce through the fog of modern and post modern life.

4. Is the research task somewhat puzzling?

4. Is the research task somewhat puzzling?

Because life is such a puzzle, we should equip young ones with the skills to weave meaning and reach insight even when confronted by baffling situations, fragments and inconclusive evidence.

The important questions are usually more difficult than a jigsaw puzzle, since the pieces and the evidence rarely fit together so cleanly. And unlike a jigsaw puzzle, such questions rarely have a single satisfying, obvious answer; nor are they two-dimensional. Baffling and puzzling are related terms. Teachers must help students to understand the emotional aspects of inquiry into realms that resist simple-minded thinking. As with adventures in the real world, there are frustrations and risks involved with authentic research.

5. Does the research task require the student to make an answer

rather than just find one?

What kind of person was Joan of Arc? Benedict Arnold? Matthew Flinders?

What kind of person was Joan of Arc? Benedict Arnold? Matthew Flinders?

What kind of leader was Joan of Arc? Benedict Arnold? Matthew Flinders?

When students are asked to build a case, take a position or construct an argument, the research process is akin to shopping for the raw ingredients that will eventually make a stew.

Authentic research demands that the student come to their own view based on evidence. What were the actions of the person they are studying that showed character? Many students might skip the hard work of gathering stories and evidence, turning instead to the opinions of others. Instead of paraphrasing and summarizing the arguments and positions of historians and commentators, students should consult primary sources whenever possible so as to collect stories and other kinds of evidence that speak to character.

When students scoop up and report the thinking of others, it is akin to buying a microwave dinner instead of cooking their stew from scratch. There is very little cooking or thinking involved. They are simply warming up the ideas of other people and skipping the construction process.

Building their own ideas is no simple matter, and their chances of success will depend somewhat upon the training an preparation provided by teachers. Examples of the skill set required for students to synthesize complex information and come up with independent conclusions can be found in these two articles:

Taking apart the ideas of others can also prove useful as training to equip students to build their own ideas. In the article "Challenging Assumptions," students learn how to deconstruct an idea and test the validity of the logic and the evidence behind that idea. A portion of that article is included here.

Picturing an Idea

Few people stop to consider what may or may not lie below the surface of an idea or proposal. In working with students, it helps to provide them with visual images of ideas along with their supporting structures. A well formed idea is a bit like an iceberg or a building. There should be plenty of logic, supporting evidence and careful thought below the surface. The idea itself may appear as a simple sentence or two but its value depends upon its foundations much like a cathedral or a sky scraper.

Few people stop to consider what may or may not lie below the surface of an idea or proposal. In working with students, it helps to provide them with visual images of ideas along with their supporting structures. A well formed idea is a bit like an iceberg or a building. There should be plenty of logic, supporting evidence and careful thought below the surface. The idea itself may appear as a simple sentence or two but its value depends upon its foundations much like a cathedral or a sky scraper.

Continuing with the building metaphor, students are encouraged to think of themselves as building inspectors. When buying a house, smart consumers pay for a housing inspection to check all parts of the house before making a final decision.

Continuing with the building metaphor, students are encouraged to think of themselves as building inspectors. When buying a house, smart consumers pay for a housing inspection to check all parts of the house before making a final decision.

|

A building inspector employs a check list. Students can employ the same approach with ideas, using the checklist provided later in this article.

The Underlying Structure of an Idea

|

We teach our students that good ideas are bolstered by three main elements:

Painting © Sarah McKenzie |

Students learn to strip away the outer coatings and veneer to see what lies below the surface of the idea. This is what we mean by teaching them to challenge assumptions. First they must first identify the assumptions. Then they must see how worthy they are.

- Do the assumptions stand up to demanding questions?

- Are the assumptions based on something more than wishful thinking? passionate belief?

- Is there abundant evidence to bolster the assumptions?

When it is their turn to conduct research and take a stand, this practice deconstructing the ideas of others will serve them well

|

|

|---|---|

Suspense is highly motivating - related in some respects to curiosity. "What will I find?" |

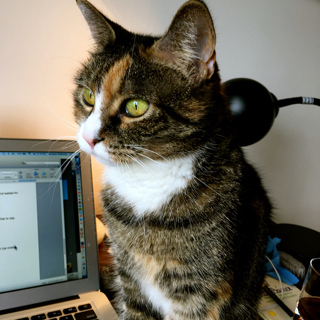

They say that curiosity killed the cat, but that's crazy. Just what is "curiosity" and how does it team with imagination to bring research to life? Good teachers know how to create cognitive dissonance and provoke curiosity.

When research is treated like earth moving, there is little drama or interest for the students, but mysteries are almost always intriguing. The teacher's job is to help students uncover the mysteries lurking behind the scenes and under the surface.

When research is treated like earth moving, there is little drama or interest for the students, but mysteries are almost always intriguing. The teacher's job is to help students uncover the mysteries lurking behind the scenes and under the surface.

7. Does the research task ask the student to come up

with a personal take, position or point of view?

Research assignments should challenge students to make up their own minds

and form their own opinions.

"What should we do about the declining salmon stocks in the Snake River?"

We expect students to do more than describe and define issues, problems and challenges. They should suggest solutions and action plans. They must do more than collect "conventional wisdom."

"Was the Great Wall of China actually a great idea?"

8. Is the research task somewhat rare, uncommon and idiosyncratic?

Some questions have been assigned for decades, over and over again. Online essay Web sites thrive selling essays designed to answer such questions. The causes of the Civil War?

Some questions have been assigned for decades, over and over again. Online essay Web sites thrive selling essays designed to answer such questions. The causes of the Civil War?

The thinking has already been done for the student . . .

Top Five Causes of the Civil War

Organizations like PBS have come up with more interesting questions to accompany the Ken Burns series of videos covering the Civil War. (List of Questions)

Many of these questions are quite open-ended and require fresh thinking along with evidence.

The Shakers during the Civil War had been called the first conscientious objectors. What does this term mean? If the US issued a draft tomorrow, which students would consider themselves conscientious objectors? Would it make a difference what the war was about? Is war morally right at certain times and morally wrong at others?

Ultimately, we would hope that individual teachers and students will formulate new questions to match the curriculum focus. Perhaps they will use questions like the PBS items mentioned above as models, but it would great to see students formulating fresh and original questions.

9. Is the research task likely to appeal to someone the age

of the students and seem intriguing and relevant to their lives?

At times it seems as if childhood is disappearing as the young are

propelled into topics and learning experiences that may be too horrific

or too complicated for them. While it might seem progressive to set

students free to study whatever they wish, one might as well let them

wander freely through the city zoo and play with the lions and tigers.

Even though powerful novels like The Boy in the Striped Pajamas have

been written about the Holocaust with young adults in mind and then

turned into even more powerful films, some of this material is extraordinarily

difficult for adults to handle. Reading such books and watching such films

is incredibly important (lest we forget), but we study these times as a way

of understanding and avoiding any repetition. Viewed at too early an age, there

is a danger that the young will find the prospects for civilization bleak.

Even when studying American history (usually repeated in 5th, 8th and 11th grades),

there are some research questions more suited for high school than elementary

school. Unfortunately, most nations have histories they would prefer to erase

or forget. While we need not immerse the fifth graders in tales of atrocities,

we could not defend whitewashing the American experience all the way

through high school.

Teachers are expected to orchestrate learning in ways that honors the sensibilities

and the developmental readiness of students.

What do 13 year old students need to know and understand?

What do 13 year old students want to know and understand?

Should anything be off bounds?

I remember my early years of teaching at the middle school level, enjoying

the powerful units on racism and prejudice included in the Greater Cleveland

Social Science Program. With all the best intentions, I showed my middle

school students the film Night and Fog. Looking back now, I think this was

too much too soon. Sometimes the curriculum planners forget in their zeal

the maturation level of the students. Ironically, a program designed to prevent

racism by asking students to confront its horrors in a direct manner may

have overstepped its bounds.

10. Is the research task likely to spark the curiosity of students?

Somewhat like a sleeping cat, sometimes curiosity is lying dormant and needs

to be awakened. At first glance the research task need not strike a student

like lightning, but a little bit of immersion should do the trick. Before long

the student is hooked. During the days of this research project she or he will

spend lots of time wondering and thinking about the task even when not formally

sitting down to conduct the research. The question or issue will simmer like a

stew on the back of a stove.

The folder icons are courtesy of Jay Boersma's site

(http://www.re-vision.com/art/gifs/icons/).

FNO Press is applying for formal copyright registration for articles.

Unauthorized abridgements are illegal.