The Mystery Curriculum

By Jamie McKenzie

About Author

Even though the most important questions in life may be to some extent unanswerable, these challenging and often frustrating issues should occupy a prominent position in the curriculum guides of schools that claim to prepare students for life in this new century. Unfortunately, perhaps because these issues are usually messy and frustrating, many schools sidestep them in favor of learning that is comfortably packaged and topics that are ripe for "plucking." Even though the most important questions in life may be to some extent unanswerable, these challenging and often frustrating issues should occupy a prominent position in the curriculum guides of schools that claim to prepare students for life in this new century. Unfortunately, perhaps because these issues are usually messy and frustrating, many schools sidestep them in favor of learning that is comfortably packaged and topics that are ripe for "plucking."

Few lists of 21st Century skills include the ability to manage ambiguity, wrestle with paradox and entertain mystery, but this failure to prepare our students for mystery is a serious lapse. The times are riddled with enigmas and conundrums. If schools adopt a mystery curriculum, students may approach these issues with familiarity and confidence instead of confusion, contempt or panic.

Mysteries vs. Puzzles

Put simply, mysteries are thornier and less cooperative than puzzles. There may not be a satisfying answer to a mystery, while most puzzles can be solved, especially those like a jigsaw. Put simply, mysteries are thornier and less cooperative than puzzles. There may not be a satisfying answer to a mystery, while most puzzles can be solved, especially those like a jigsaw.

Malcolm Goodwells’s article in the New Yorker (January 8, 2007) about Enron’s mystifying accounting challenges, “Open Secrets," makes this point dramatically. He credits the national-security expert Gregory Treverton:

- (Treverton) has famously made a distinction between puzzles and mysteries.

- Osama bin Laden’s whereabouts are a puzzle. We can’t find him because we don’t have enough information. The key to the puzzle will probably come from someone close to bin Laden, and until we can find that source bin Laden will remain at large.

- The problem of what would happen in Iraq after the toppling of Saddam Hussein was, by contrast, a mystery. It wasn’t a question that had a simple, factual answer. Mysteries require judgments and the assessment of uncertainty.

Examples

Even though students around the world may study the events of the Second World War and the horrors of Auschwitz - the extermination of millions of Jews, Gypsies and others - some of the most mysterious and troubling questions embedded in this history may go unexamined in some classrooms.

- How do leaders persuade citizens to go along with such horrors?

- Can genocide be stopped by those caught up in it?

- What kinds of people are willing to participate in the actual slaughter?

- What kinds of people are willing to look the other way and pretend nothing is happening?

- Are we looking the other way right now?

- Where is genocide happening today and what are we doing about it?

- What does it take to stop such horrors from continuing in our own times?

- In what ways can religion play a role in encouraging such horrors? or discouraging them?

- How does the UN define genocide?

- Have we been guilty of genocide?

- What does it take to survive?

- How do the survivors cope?

- How can the world best bring justice to those who perpetrated genocide?

- Will these questions persist for centuries more?

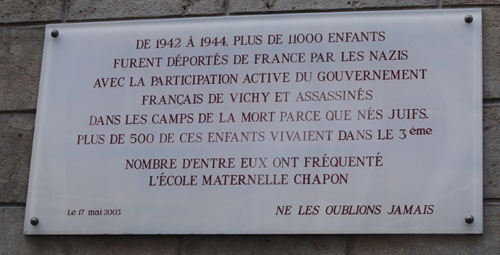

11,000 Jewish Children from Paris Killed between 1942-44

How could something like this happen? Just imagine! 11,000 children shipped off to concentration camps and slaughtered.

One day I was strolling through Paris enjoying a sunny afternoon when I passed L'École Maternelle Chapon and saw the plaque pictured above. "Let us never forget them," the plaque reads, placed there in May of 2003.

While we would like to think that such madness is a thing of the past and that genocide is practiced by others, current events offer plenty of examples of mass slaughter and nearly every country has been complicit at some time in some form of mass slaughter, including the slaughter of innocents.

Fear of Darkness

One reason some schools may shy away from such issues and questions is the controversial and often troubling nature of the material. A month spent wrestling with such questions may result in little peace, almost no certainty and precious little resolution. Young ones can become troubled and distressed by these kinds of inquiries. There are few happy endings, in the Hollywood sense. There is a clear and present danger of disillusionment, angst and depression.

These same risks may partially explain how news programs can focus more attention on the antics of Paris Hilton than on the events in Darfur. Even the coverage of Iraq has declined dramatically in recent months (Note Pew Study). Certain news sells poorly and wins no audience.

- The three TV broadcast networks' nightly newscasts devoted more than 4,100 minutes to Iraq in 2003 and 3,000 in 2004, before leveling off at about 2,000 a year, according to Andrew Tyndall, who monitors the broadcasts and posts detailed breakdowns at tyndallreport.com. But by the last months of 2007, he said, the broadcasts were spending just half as much time on Iraq as they had earlier in the year.

But some puzzles and enigmas are less dark and hardly troubling. They may not prove any more easily resolved, but these pleasant mysteries win little attention except in whimsical and fleeting dalliances as in an English class that considers a poem for a few minutes. Poets have been fond of mysteries, both dark and amusing ones, for centuries, but a few moments of whimsey hardly prepare young ones for a lifetime of mysteries.

- In Just-

spring when the world is mud-

luscious the little

lame balloonman

whistles far and wee

-

- E.E.Cummings

What's it all about?

The recent obsession with reading and math in the USA fostered by the narrow minded NCLB law has turned attention away from serious problems with comprehension, understanding and thinking skills that have plagued us for decades when measured by the NAEP tests - the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Note article, "Adolescent Literacy: Putting the Crisis in Context" by Jacobs, Vicki A, in the Spring 2008 issue of The Harvard Educational Review.

As the short-sighted and intellectually bankrupt strategies of NCLB become evident to those who transformed much of schooling into drill and practice for basic skills tests, we can now hope and wish for a return to an approach to learning that makes adolescent literacy in the broad sense a priority. Unless we are teaching the young to wrestle with mystery and manage complexity, they are unlikely to meet the challenges of this century with skill and confidence. A public that has been raised on the thin gruel of learning that was focussed on simple test taking is unlikely to handle the tough ideas and concepts required for thoughtful citizenship during troubling times. Raised on simple answers for simple tests, there is every danger that they will seek the same simplicity from their leaders - simple answers for complex problems.

|

Even though the most important questions in life may be to some extent unanswerable, these challenging and often frustrating issues should occupy a prominent position in the curriculum guides of schools that claim to prepare students for life in this new century. Unfortunately, perhaps because these issues are usually messy and frustrating, many schools sidestep them in favor of learning that is comfortably packaged and topics that are ripe for "plucking."

Even though the most important questions in life may be to some extent unanswerable, these challenging and often frustrating issues should occupy a prominent position in the curriculum guides of schools that claim to prepare students for life in this new century. Unfortunately, perhaps because these issues are usually messy and frustrating, many schools sidestep them in favor of learning that is comfortably packaged and topics that are ripe for "plucking."

Put simply, mysteries are thornier and less cooperative than puzzles. There may not be a satisfying answer to a mystery, while most puzzles can be solved, especially those like a jigsaw.

Put simply, mysteries are thornier and less cooperative than puzzles. There may not be a satisfying answer to a mystery, while most puzzles can be solved, especially those like a jigsaw.