| Research Cycle |

|

|

|

| Vol 9|No4|April |2013 | |

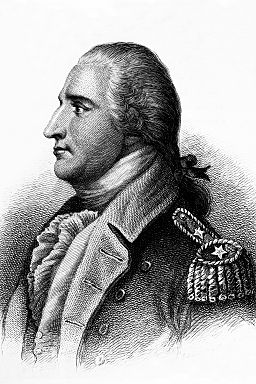

Unmasking Iconic Figures

Benedict Arnold |

|

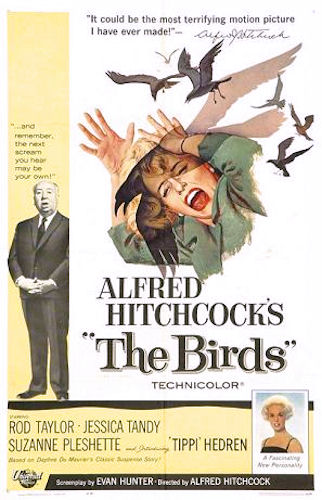

Alfred Hitchcock |

||

When our students learn about important people in history as well as figures from their own times, we would expect them to scratch away at the superficial, iconic images easily at hand to learn more about the person behind the mask. Changing Research Rituals In many schools, research about important people usually requires little more than hunting and gathering, scooping and smushing. The student is expected to gather key factoids.

This search for basic information requires little time, skill or thought. The student ends up with an iconic view of the person. Google quickly directs the student to a Hitchcock biography where all the answers can be found. There is little mystery or drama. And the biography is silent on Hitchcock's many flaws and possible sexual harassment of actresses. Nothing is said about drunken behavior or poor treatment of those who worked with him. The image of the man is incomplete and false.

Biography Questions of ImportIn contrast, when students are asked to explore questions of import, the research is much more engaging, challenging and rewarding.

The Biography MakerThe above questions can be found embedded in The Biography Maker - a Web-based learning resource I developed nearly twenty years ago to help students change the way they approach the research and the writing of biographies. Updated in 2005, The Biography Maker takes students through a sequence of that begins with questions and then ends with synthesis and effective writing. 1. Questioning | 2. Learning | 3. Synthesis | 4. Story-Telling The Importance of Unmasking

In learning about figures like Alfred Hitchcock, it helps to acquaint students with the role of publicists. According to The Encyclopedia of American Cinema, Hitchcock hired his first publicist in 1926 while enjoying early success directing films in Great Britain. What does a publicist do? He or she helps the celebrity or the politician to create favorable images with the media. Sometimes called a "spin doctor," the publicist works with the client to decide which masks to share with the public.

The movie explores the issue of his leading ladies without ever taking a clear stance. Reading through other sources, one finds charges, complaints and allegations of misconduct, but one also finds conflicting testimony. How credible is the movie? One need only read one interview with the actress playing Hitchcock's secretary to learn that there was very little factual information upon which to base her interpretation of the character. (Interview: Toni Collette)

When we are allowed to listen to conversations between Hitchcock and his wife or various other characters, it is unlikely that a tape recorder was present to capture the actual words, so those dialogues are Hollywood creations about the conversations of Hollywood creations. Students must learn to see these movies as impressionistic. When there is scant factual evidence upon which to base scenes and conversations, the imagination is allowed to fill in the blanks. This is a form of poetic license that makes for great stories and movies but may distort the truth in dramatic ways.

Interesting to contrast these recent claims with her words in a 1963 interview that can be seen on YouTube. She is asked if Hitchcock was a difficult man to work with, and she answers, "Not at all. I've never heard him raise his voice, or . . . temperament. He has no great show of temperament. whatsoever. He's wonderful to work with." After the release of The Girl in 2012 Hedren spoke bitterly of Hitchcock in an interview with Huffington Post. "Tippi Hedren: Hitchcock Ruined My Career." According to the biography upon which the movie The Girl was based, Spellbound by beauty: Alfred Hitchcock and his leading ladies by Donald Spoto, Hedren recalls a conversation with Hitchcock during which he demanded sexual favors in exchange for continued star roles. She claims that he threatened to ruin her career if she refused and did just that, holding her prisoner to her contract when she turned him down.

In those days there was no real way to report sexual harassment or sue the person using power to get favors. Victims were faced with difficult choices. Fifty years after these events, the allegations are finally surfacing. Spoto does a convincing job of documenting Hitchcock's longstanding difficulties with actresses. The Girl begins with a scene showing Hedren in her first interview with Hitchcock during which he invites her to join him for lunch in his office, pours her a glass of pinot noir and shares a limerick that is heavily laced with sexual innuendo. Did this conversation ever take place? How would we know? Can we take Hedren's word for it? Or should we give Hitchcock a chance to defend himself? Is this a case of "He says — She says?" Is the scene apocryphal?

Spoto documents that Hitchcock's use of sexual limericks were reported by quite a few of the young women who he had under contract. So while the specific limerick may be unsubstantiated, his offensive pattern has been substantiated. A boss in the current American workplace would face severe consequences for such behavior. A bit later in the movie we hear Hitchcock directing Hedren in what seems like the screen test for The Birds. But you can see the real screen test on YouTube and The Girl changes it dramatically to make Hitchcock seem quite strange, giving him far more lines. He is heavy handed in the screen test, directing her every move. In the actual screen test he says little, and Hedren is a very impressive, charismatic young woman strutting her stuff with great élan. Considering she had not acted previously but was a successful fashion model, her performance is very strong. In the movie she is a bit bewildered and tossed about by his commands — a victim, an innocent. Here we have a case of historical fact standing alongside an HBO dramatization. Students should be able to see the contrast between fact and fiction. Sorting through claims and counter claims is necessary whether we are looking at the life of Joan of Arc, Benedict Arnold, Bill Clinton or Alfred Hitchcock. The Power of Triangulation

One of Hitchcock's biographers, Patrick Mcgilligan, points out that illusion was Hitchcock's forte:

Short biographies of Hitchcock tend to paint his childhood in broad, mostly dark strokes relying for evidence upon a story Hitchcock repeated hundreds of times over the years about being sent at the age of five to the local police station as a warning about what happens to bad boys.

Patrick Mcgilligan devotes several pages to a more balanced view of Hitchcock's early family life.

Middle and high school students are capable of digging past the short biographies and using triangulation to compare versions of various stories. Knowing that Hitchcock was an inveterate story teller who took pride in embellishing and amplifying the original events and circumstances to create the impression (or illusion) that served his career purposes, the students consult a half dozen or more sources to see whether they are consistent. Patrick Mcgilligan does this when he compares the household descriptions of Donald Spoto, in his “dark” biography of Hitchcock, with the descriptions offered by Hitchcock's authorized biographer, John Russell Taylor.

A student does not have to read all of the biographies to get a taste of the inconsistencies. He or she can select one aspect of Hitchcock's life like his childhood and compare what the various sources say. Perhaps they will examine the claim that he treated actors poorly. Maybe they will look at allegations of sexual misconduct. Whatever slice they select may leave them shaking their heads in confusion. Spoto's book presents a strong case against Hitchcock, but others like Ron Miller offer conflicting evidence. In "Alfred Hitchcock: Did He Really Treat Actors Like Cattle?" he quotes many actors who told him mainly positive things about Hitchcock. The contrast with Spoto's book is dramatic.

Who are we to believe? Who is the most credible? Who presents the most telling evidence? Veracity: Learning to appreciate ambiguity, enigma, and complexity Ironically, when the researcher leaves the safety and simplicity of the iconic biography, he or she will find the character enigmatic. The clarity of icons is replaced by fog, ambiguity and conjecture. The student learns that no person matches his or her publicity releases. The student sees that even regular folks conceal much of their inner lives even from those people closest to them. They come to see that iconic images are false. While this is disillusioning in some ways, it is also liberating. In their reading of novels like Heart of Darkness, The Great Gatsby and Jane Austen, they see that human character is multi-layered and complex. In their study of figures from Hollywood, they learn that masters of suspense and mystery often apply their dramatic skills to the way they project themselves to the public. |

||||

Copyright Policy: Materials published in The Question Mark may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by email. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. FNO Press is applying for formal copyright registration for articles.

|

||||

Watching the new movie about Alfred Hitchcock —

Watching the new movie about Alfred Hitchcock —

As the director of many horror films, Hitchcock actively cultivated an image that accentuated the bizarre and the horrific. Peeling away layers of purposeful image making proves difficult. The Hitchcock movie purports to give us an inside view of Hitchcock's life and marriage at the time he was filming Psycho, but how much of this is speculation? Once students have scoured online biographies, they are faced with what might be an impossible task. Hitchcock's internal life is not well documented. And because many of his relationships with actors were intense, they are surrounded by rumors and innuendo.

As the director of many horror films, Hitchcock actively cultivated an image that accentuated the bizarre and the horrific. Peeling away layers of purposeful image making proves difficult. The Hitchcock movie purports to give us an inside view of Hitchcock's life and marriage at the time he was filming Psycho, but how much of this is speculation? Once students have scoured online biographies, they are faced with what might be an impossible task. Hitchcock's internal life is not well documented. And because many of his relationships with actors were intense, they are surrounded by rumors and innuendo. Upon the release of another Hitchcock movie in 2012, The Girl, new allegations surfaced as actress Tippi Hedren, blond star of The Birds, accused Hitchcock of sexual harassment

Upon the release of another Hitchcock movie in 2012, The Girl, new allegations surfaced as actress Tippi Hedren, blond star of The Birds, accused Hitchcock of sexual harassment