The Questioning Toolkit - Revised

by Jamie McKenzie (about author)

The first version of the Questioning Toolkit was published in November of 1997. Since then there has been substantial revision of its major question types and how they may function as an interwoven system.

This article takes the model quite a few steps further, explaining more about each type of question and how it might support the overall investigative process in combination with the other types.

photo ©istockphoto.com

Section One - Orchestration

Most complicated issues and challenges require the researcher to apply quite a few different types of questions when building an answer. These types of questions must be carefully selected to match the task at hand, just as one might pick a saw instead of a hammer when it is time to cut a plank of wood.

Orchestration is the key concept added to the model since its first version.

orchestrate:

To combine and adapt in order to attain a particular effect: arrange, blend, coordinate, harmonize, integrate, synthesize, unify.

Roget’s II: The New Thesaurus. 1995.

The skilled questioner knows which types of questions to ask to accomplish each phase of an investigation and understands how to orchestrate the various types so they work together to bring clarity and understanding to the matter being examined.

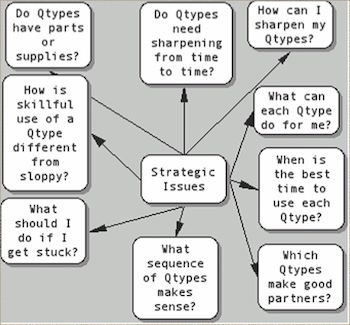

The thinker must consider a number of strategic issues on a continuing basis while gathering information and exploring. On the next page, some of these issues are shown in a cluster diagram. The careful consideration of these issues leads to skillful orchestration rather than haphazard wandering.

As the researcher moves beyond mere gathering to discovering and inventing new meanings, the complexity and the challenge of effective orchestration grows dramatically.

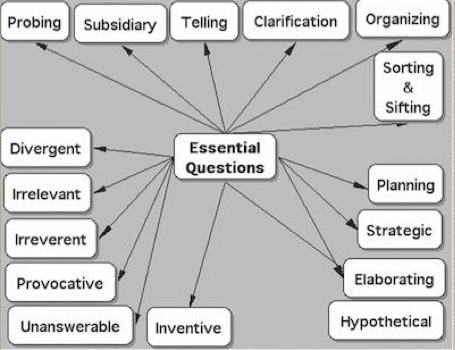

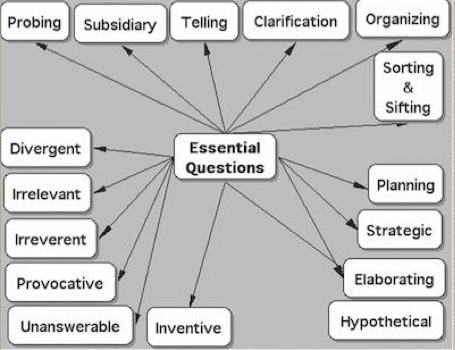

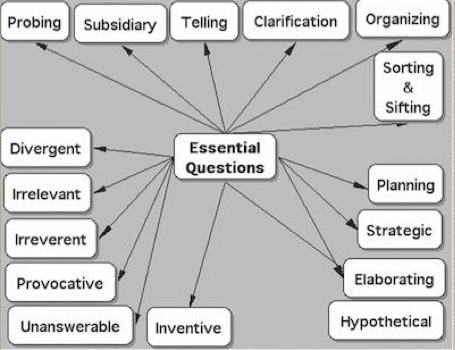

Recognizing the importance and the interplay between these strategies and the various question types (Qtypes) led to a significant revision of the original Questioning Toolkit. As orchestration suggests the importance of grouping the question types by function, we see a new pattern emerge with three groups of question types:

- Question types that involve digging (top)

- Question types that involve planning (right)

- Question types that involve invention (bottom left)

This organization of the pattern enhances the importance of sequence, function and orchestration.

We look to schools and teachers to make exploration and inquiry with these kinds of questioning strategies a prime focus of activity so students will emerge from their education as thinkers and inventors, no matter what their choice of vocation and avocation.

If they elect fashion design, we would hope to see them approach the challenge with originality and insight. Not every designer has the chance to invent a swim suit that cuts time off an Olympic swimmer’s world record, but there are variations on the theme on every level of the enterprise.

Likewise, if they pick software or hair design, we would hope that they would consider the task with a view toward elegance and harmony. Designing a building? a basket? a flower arrangement? Again, we would hope that they would consider the task with a consideration of simplicity and grace.

photo ©istockphoto.com

I recall a conversation with a carpenter several decades back who helped my family convert a garage into a bedroom for my young daughters. This carpenter spoke of the wood he chose for a staircase railing with a reverence that impressed and surprised me, as his selection came after signing a contract that left little room for top quality lumber. This special wood for the railing would come out of his own pocket. But he approached the room as a creation, almost as a sculptor would. By selecting this wood, he was making his mark as an inventor and an artist. By selecting special wood, he was setting himself apart from that “one more brick in the wall” trap so vividly portrayed by Pink Floyd.

After more than four decades of working with children in schools, I have come to believe we have expected too little of many children and have often failed to recognize the potential that nearly all students have to think and perform in magical ways. We have been grading and thinking for too long within the confines of the normal curve, looking for exceptionality at the outer edges rather than assuming its presence along the the continuum. When the normal curve becomes conventional wisdom, schools end up leaving many children behind.

photo ©istockphoto.com

Section Two - Each Type Defined

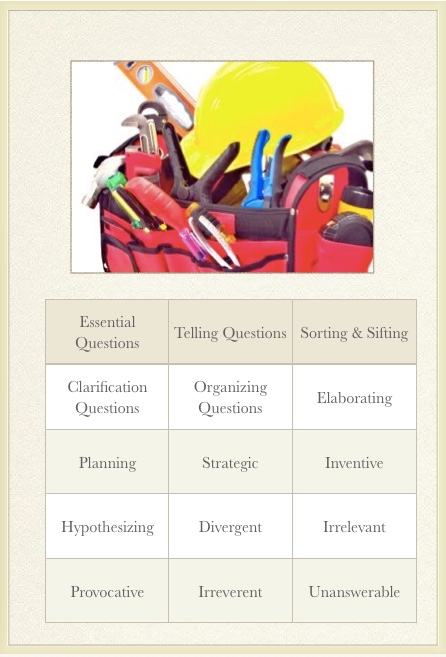

Each district should create a Questioning Toolkit containing several dozen kinds of questions and questioning tools. This Questioning Toolkit should be displayed on large posters on classroom walls where they can be seen easily.

Portions of the Questioning Toolkit should be introduced as early as Kindergarten so that students can bring powerful questioning technologies and techniques with them as they arrive in high school.

--- Essential Questions ---

These are questions that touch our hearts and souls. They are central to our lives. They help to define what it means to be human.

Most important thought during our lives will center on such essential questions.

- What does it mean to be a good friend?

- What kind of friend shall I be?

- Who will I include in my circle of friends?

- How shall I treat my friends?

- How do I cope with the loss of a friend?

- What can I learn about friends and friendships from the novels we read in school?

- How can I be a better friend?

When we create a cluster diagram of the Questioning Toolkit, Essential Questions sit at the center of all the other types of questions. All the other questions and questioning skills serve the purpose of "casting light upon" or illuminating Essential Questions. Most Essential Questions are interdisciplinary in nature. They cut across the lines created by schools and scholars to mark the terrain of departments and disciplines.

Essential Questions probe the deepest issues confronting us — complex and baffling matters that elude simple answers: Life - Death - Marriage - Identity - Purpose - Betrayal - Honor - Integrity - Courage - Temptation - Faith - Leadership - Addiction - Invention - Inspiration.

The greatest novels, the greatest plays, the greatest songs and the greatest paintings all explore Essential Questions in some manner.

Essential Questions are at the heart of the search for Truth.

Many of us believe that schools should devote more time to Essential Questions and less time to Trivial Pursuit.

One major reform effort, the Coalition of Essential Schools, made Essential Questions a keystone of its learning strategy.

Essential Questions offer the organizing focus for a unit — sometimes for a year. If the U.S. History class will spend a month on a topic such as the Civil War, students explore the events and the experience with a mind toward casting light upon one of the following questions, or they develop Essential Questions of their own . . .

- Why do we have to fight wars?

- Do we have to fight wars?

- How could political issues or ideas ever become more important than family loyalties?

- Some say our country remains wounded by the slavery experience and the Civil War. In what ways might this claim be true and in what ways untrue? What evidence can you supply to substantiate your case?

- Military officers often complain that the effective conduct of modern war is impeded by political interference and popular pressures on the home front. To what extent did this also prove true during the Civil War?

- How can countries avoid the kind of bloodshed and devastation we experienced during our Civil War?

- How much diversity can any nation tolerate?

- Who showed greater bravery and courage, the front line soldiers and the nurses who tended to the wounded and dying or the leaders of the war effort?

Different types of questions accomplish different tasks and help us to build up our answers in different ways.

We must show our students the features of each type of question so they know which combination to employ with the essential question at hand. We don't want them reaching into their toolkit blindly, grasping the first question that comes to mind.

No sense grabbing a screw driver when a wrench is needed. No use seizing the hammer when a saw is required. We want them to reach for the question that matches the job.

-

-- Telling Questions ---

Telling Questions lead us (like a smart bomb) right to the target. They are built with such precision that they provide sorting and sifting during the gathering or discovery process. They focus the investigation so that we gather only the very specific evidence and information we require — only those facts that "cast light upon" or illuminate the main question at hand.

In schools that give students e-mail accounts, what is the rate of suspension for abusing the privilege?

In schools which give students e-mail accounts, what percentage of students lose their privilege during each of the first ten months? second ten months?

The better the list of telling questions generated by the researcher, the more efficient and pointed the subsequent searching and gathering process. A search strategy may be profoundly shifted by the development of telling questions.

Students trying to rank the relative safety of ten cities in the Heartland will have greater success with their search if they translate their general question about crime “Which city is safest?” into a Telling Question — “What is the violent crime rate for cities in the Heartland as reported by the Federal Bureau of Justice and how has it changed over the past ten years?” These telling questions work best when students make use of the advanced version of a search engine as outlined in the article, “Searching for the Grail.”

--- Planning Questions ---

Planning Questions lift us above the action of the moment and require that we think about how we will structure our search, where we will look and what resources we might use such as time and information. If we were sailing West on a square masted ship, we would pass off the wheel and the lines to team-mates in order to climb to the "crow's nest" - a lofty perch from which we could look "over the horizon."

Too many researchers, be they student or adult, make the mistake of burying their noses in their studies and their sources. They have trouble seeing the forest, so close do they stand to the pine needles. They are easily lost in a thicket of possibilities.

The effective researcher develops a plan of action in response to Planning Questions like the following . . .

Sources

- Who has done the best work on this subject?

- Which group may have gathered the best information?

- Which medium (Internet, electronic periodical collection, scholarly book, etc.) is likely to provide the most reliable and relevant information with optimal efficiency?

- Which search tool or index will speed the discovery process?

Sequence

- What are all of the tasks that need completing in order to generate a credible product that offers fresh thought backed by solid evidence and sound thinking?

- What is the best way to organize these tasks over time? How much time is available? Which tasks come first, and then . . .?

- Which tasks depend upon others or cannot be completed until others are finished?

Pacing

- How much time is available for this project?

- How long does it take to complete each of the tasks required?

- How much time can be applied to each task?

- Do some tasks require more care and attention than others?

- Can some tasks be rushed?

- Is it possible to complete the project in the time available?

- How should the plan be changed to match the time resources?

--- Organizing Questions ---

Organizing Questions make it possible to structure our findings into categories that will allow us to construct meaning. Without these structures we suffer from hodgepodge and mishmash — information collections akin to trash heaps and landfills, large in mass, lacking in meaning. The less structure we create in the beginning, the harder it becomes later to find patterns and relationships in the fragments or the collection of bits and pieces.

If we are trying to compare and contrast three cities (or three products or three bills or three artists) we might use our criteria and our telling questions as the basis for the sections of our mind map. In a recent professional development session on laptop writing and thinking, participants organized their findings as the map shows on the previous page. Our challenge is teaching students to paraphrase, condense and then place their findings thoughtfully rather than cutting and pasting huge blocks of text which have been unread, undigested and undistilled.

photo ©istockphoto.com

--- Probing Questions ---

Probing Questions take us below the surface to the "heart of the matter." They operate somewhat like the archeologist's tools - the brushes that clear away the surface dust and the knives that cut through the accumulated grime and debris to reveal the outlines and ridges of some treasure.

Another appropriate metaphor might be exploratory surgery. The good doctor spends little time on the surface, knowing full well that the vital organs reside at a deeper level.

“We never stop investigating. We are never satisfied that we know enough to get by. Every question we answer leads on to another question. This has become the greatest survival trick of our species."

Desmond Morris - The Naked Ape

The search for insight involves some of the same exploratory elements. Probing Questions allow us to push search strategies well beyond the broad topical search to something far more pointed and powerful.

And when we first encounter an information "site," we rarely find the treasures lying out in the open within easy reach. We may need to "feel for the vein" much as the lab technician tests before drawing blood. This "feeling" is part logic, part prior knowledge, part intuition and part trial-and-error.

Logic — We check to see if there is any structure to the way the information is organized and displayed, if there are any sign posts or clues pointing to where the best information resides. We assume the author had some plan or design to guide placement of information and we try to identify its outlines.

Prior Knowledge — We apply what we have seen and known in the past to guide our search. We consider information about the topic and prior experience with information sites. This prior knowledge helps us to avoid dead ends and blind alleys. It helps us to make wise choices when browsing through lists of "hits." Prior knowledge also makes it easier to interpret new findings, to place them into a context and distinguish between "fool's gold" and the real thing.

Intuition — We explore our hunches, follow our instincts, look for patterns and connections, and make those leaps our minds can manage. Especially when we are hoping to create new knowledge and carve out new insights, this non-rational, non-logical form of information harvesting is critically important.

Trial-and-Error — Sometimes, nothing works better than plain old "mucking about." Push here. Tug there. Try this out! We find a site with so much information and so little structure that we have little choice but to plunge in and see what we can find.

--- Sorting and Sifting Questions ---

Sorting and Sifting Questions enable us to manage Info-Glut and Info-Garbage - the thousands of hits and pages and files that often rise to the surface when we conduct a search - culling and keeping only the information that is pertinent and useful.

Relevancy is the primary criterion employed to determine which pieces of information are saved and which are tossed overboard. We create a "net" of questions that allows all but the most important information to slide away. We then place the good information with the questions it illuminates.

- Which parts of this data are worth keeping?

- Will this information shed light on any of my questions?

- Is this information reliable?

- How much of this information do I need to place in my mind map?

- How can I summarize the best information and ideas?

- Are there any especially good quotations to collect?

--- Clarification Questions ---

Clarification Questions convert fog and smog into meaning. A collection of facts and opinions does not always make sense by itself. Hits do not equal TRUTH. A mountain of information may do more to block understanding than promote it. Defining words and concepts is central to this clarification process. Examining the coherence and logic of an argument, an article, an essay, an editorial or a presentation is fundamental.

- How did they develop the case they are presenting?

- What is the sequence of ideas and how do they relate one to another?

- Do the ideas logically follow one from the other?

Determining the underlying assumptions is vital.

- How did they get to this point?

- Are there any questionable assumptions below the surface or at the foundation of the argument?

"Clever people seem not to feel the natural pleasure of bewilderment, and are always answering questions when the chief relish of a life is to go on asking them."

Frank Moore Colby - The Colby Essays, vol. 1, "Simple Simon" (1926)

--- Strategic Questions ---

Strategic Questions focus on ways to make meaning. The researcher switches from tool to tool and from strategy to strategy while passing through unfamiliar territory. Closely associated with the Planning Questions formulated early on in this process, Strategic Questions arise during the actual hunting, gathering, inferring, synthesizing and ongoing questioning process.

- What do I do next?

- How can I best approach this next step?, this next challenge? this next frustration?

- What thinking tool is most apt to help me here?

- What have I done when I've been here before? What worked or didn't work? What have others tried before me?

- What type of question would help me most with this task?

- How do I need to change my research plan?

--- Elaborating Questions ---

Elaborating Questions extend and stretch the import of what we are finding. They take the explicit and see where it might lead. They also help us to plumb below surface to implicit (unstated) meanings.

- What does this mean?

- What might it mean if certain conditions and circumstances changed?

- How could I take this farther? What is the logical next step? What is missing? What needs to be filled in?

- Reading between the lines, what does this really mean?

- What are the implied or suggested meanings?

--- Unanswerable Questions ---

Unanswerable Questions are the ultimate challenge.

They serve like boundary stones, helping to tell us when we have pushed insight to its outer limits. When exploring essential questions (most of which are unanswerable in the ultimate sense) we may have to settle for "casting light" upon them. When wrestling with these Unanswerable Questions we may never find Truth, but we may illuminate — extend the level of our understanding and reduce the intensity of the darkness.

"The real questions are the ones that obtrude upon your consciousness whether you like it or not — the ones that make your mind start vibrating like a jackhammer, the ones that you "come to terms with" only to discover that they are still there. Real questions refuse to be placated. They barge into your life at times when it seems most important for them to stay away. They are the questions asked most frequently and answered most inadequately, the ones that reveal their true natures slowly, reluctantly, most often against your will."

Ingrid Bengis - Combat in the Erogenous Zone, "Man-Hating" (1973)

- How will I be remembered?

- How much can anyone resist Fate's will?

- What is the Good Life?

- What is friendship?

- How would life be different if . . .

Students wrestling with Essential Questions must be prepared for the likelihood that their questions may be Unanswerable. They must be taught that this reality is normal and is not a signal to stop searching and thinking.

--- Inventive Questions ---

Inventive Questions turn our findings inside out and upside down. They distort, modify, adjust, rearrange, alter, twist and turn the bits and pieces we have picked up along the way until we can shout "Aha!" and proclaim the discovery of something brand new.

- How do I make sense of these bits and bytes and pieces?

- What does all this information really mean?

- How can I rearrange what I have gathered so that some picture or new insight emerges?

- What needs to be eliminated, reversed or modified in order to make better sense of my findings?

- What is still missing?

- Can any information be regrouped or combined in ways which help meaning to emerge?

- Can I display this information or data in a way which will cast more light on my essential question?

--- Provocative Questions ---

Provocative Questions are meant to push, to challenge and to throw conventional wisdom off balance. They give free rein to doubt, disbelief and skepticism.

"The best servants of the people, like the best valets, must whisper unpleasant truths in the master's ear. It is the court fool, not the foolish courtier, whom the king can least afford to lose."

Walter Lippmann - A Preface to Politics, ch. 6 (1914).

Ancient empires and kingdoms in China often employed a court jester or fool whose job it was to challenge and make fun of policies, ideas and key players surrounding the king or queen. The fool could often get away with a level of questioning that would never be permitted a "legitimate" member of the council. On the other hand, the fool might also lose his head if the king or queen took offense. A dangerous occupation!

Closely associated with Divergent Questions and Irreverent Questions, Provocative Questions help provide the basis for satire, parody, and expose — whether it be

Gulliver's Travels,

Alice in Wonderland,

DILBERT or Seymour Hersh's

The Dark Side of Camelot. These plays and stories poke fun at politicians and leaders in ways that help protect us from “excessive deference or what is fondly called "spin" today.

In the case of student research, we have probably devoted too little attention to the role of irony, satire and parody as important elements in "open systems" — a term that describes responsive (and healthy) political systems as well as organizations of various kinds such as schools and corporations.

When inspired by a desire to understand the Truth, Provocative Questions play a positive role in debunking propaganda, mythologies, hype, bandwagons and the Big Lie. They help us to remove the "bunk" or "claptrap" and determine if there is any substance worth considering. In a time of what Toffler calls "info-tactics," such questions become an essential tool for any citizen in a democratic society.

In an age of info-glut and info-garbage, we must equip students with questions that enable them to separate out meaning from all the competing variants of BLATHER quoted here from Roget's Thesaurus . . .

“empty talk, idle speeches, sweet nothings, endearments, wind, gas, hot air, vaporing, verbiage, DIFFUSENESS

rant, ranting and raving, bombast, fustian, rodomontade, BOASTING

blether, blather, blah-blah-blah, flimflam

guff, hogwash, eyewash, claptrap, poppycock, FABLE

humbug, FALSEHOOD

malarkey, hokum, bunkum, bunk, baloney, hooey

flummery, blarney, FLATTERY

sales talk, patter, sales patter, spiel

chatter, prattle, prating, yammering, babble, gabble, jabber, jibber jabber, jaw, yackety-yak, yak yak, rhubarb, CHATTER

- Where's the beef? content? substance? logic? evidence?

- What is the source? Is the source reliable?

- What's the point? Is there a point?

- Cutting past the noise and the rhetoric, is there any insight, knowledge or worthwhile information here?

--- (Apparently) Irrelevant Questions ---

Irrelevant Questions take us far afield, distract us and threaten to divert us from the task at hand. And that is their beauty!

Truth almost never appears where we might look logically. The creation of new knowledge almost always requires some wandering off course. The more we cling to coastline, the less likely we are to find any New World. As Melville so dramatically pointed out in Moby Dick, the search for Truth requires the courage to venture out and away from the familiar and the known:

But as in landlessness alone resides the highest truth, shoreless, indefinite as God --so, better is it to perish in that howling infinite, than be ingloriously dashed upon the lee, even if that were safety!

For an expanded explanation of Irrelevant Questions, go to this article.

--- Divergent Questions ---

Divergent Questions use existing knowledge as a base from which to "kick off" like a swimmer making a turn. They move more logically from the core of conventional knowledge and experience than irrelevant questions. They are more carefully planned to explore territory which is adjacent to that which is known or understood.

Trying to find a way to restore water quality in a lake or stream? If we limit our search to successful attempts, we may miss out on the chance to avoid other people's mistakes.

Sometimes we learn more by studying the opposite of our main target.

In the same sense, we may want to check out efforts to restore air quality and other tangentially related efforts. We may even explore efforts to re-introduce endangered species to various habitats. New ideas are rarely sitting waiting for us in obvious places.

The ability to associate related topics and questions freely greatly increases the odds that researchers will make important discoveries.

--- Irreverent Questions ---

Irreverent Questions explore territory that is "off-limits" or taboo. They challenge far more than conventional wisdom. They hold little respect for authority, institutions or myths. They leap over, under or through walls, rules and regulations.

Socrates found himself in considerable trouble for showing the youth of Athens how to ask Irreverent Questions, and we need to remember that such questions are not universally appreciated. In fact, some folks find such questioning disrespectful and impolite. They question the value of Irreverent Questions.

It is the human condition to question one god after another, one appearance after another, or better, one apparition after another, always pursuing the truth of the imagination, which is not the same as the truth of appearance.

Alain [Émile-Auguste Chartier - The Gods

Corporations such as IBM have learned that today's heretic — the one with the courage, the tenacity and the brash conviction to question the way things are "spozed to be" —often turns out to be a prophet of sorts. The Emperor's New Clothes is the classic story showing what happens when Irreverent Questions are discouraged and obedience, subservience and compliance are prized. The emperor parades naked. The corporation clings blindly to old beliefs.

The Great Report

You can read sample chapters and see the list of chapters by clicking here.

Order the print version by clicking below.

Order through the mail with a check, click here for the order form.