| Research Cycle |

Order Kindle versions of Jamie's books

Order Jamie's books online with Paypal or a credit card

|

|

|

| Vol 11|No1|October |2014 | |

This image is from iStock.com |

Questioning luck,

|

|||||||||

How much of our fate is predetermined, and how much is shaped by our efforts? This is an important issue for students to explore as they chart their futures — one that teachers and schools should raise deliberately so as to increase the likelihood that students will emerge from school feeling efficacious. Efficacious? It means feeling capable of getting things done, of accomplishing things through one's efforts as opposed to sitting around and hoping for good luck. Psychologists divide people into two groups — those with an "internal locus of control" and those with an "external locus of control." The first group feels they make things happen, that their fate is a matter of their own choice and efforts. The second group believes that their fate is largely a matter of luck or is determined by powerful others. And then there are some people spread across the middle of the spectrum, feeling a mix of both attitudes. As life hands out its surprises, rewards and disappointments, a person can switch from internal to external and back again. As one site puts it, "Are you in control of your destiny?" or do you feel that there is someone else pulling the strings? [Mind Tools] On that site you can take an interactive quiz to determine your current locus of control. Attitudes about control can shift with time and experience, as things may not go so well for a year or two and even those with an internal locus of control may become disheartened, disillusioned and defeated. The reverse may also happen. Someone with an external locus of control may see their efforts at school or work rewarded in ways that make them start to believe in themselves. What does luck have to do with it? Almost everyone believes in luck to a certain extent. We say things like, "This was not my lucky day." Or we say, "As luck would have it . . . " The list goes on:

There are many times when our efforts are simply not enough to bring about the result we seek. We may be taking a chance. We may be investing in something that involves risk. The statistics may count against us. Our chances may not be good. But then, all of a sudden, despite the statistics and the unfavorable odds, we get some good luck. Our photograph goes viral. We knew it was good, but we never dreamed it would be viewed by thousands. Was this luck? Good fortune? It happened to me with the photo and poem below. 7,674 views when this article went to press.

Turning to Habits of Mind Art Costa's Habits of Mind is a powerful model to help students to understand the interplay between personal efforts and happenstance. Quoting from the Costa Web site:

Two of these (in bold above) are especially relevant to the issue of luck. If you read Art Costa's extended descriptions from Chapter Two of his book, Learning and Leading with Habits of Mind, edited by Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick, you will see how directly they apply:

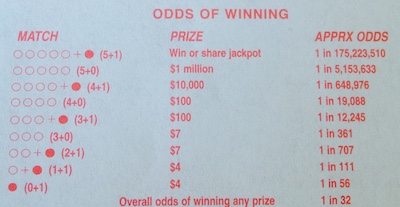

Judging the odds of winning Students must learn to calculate the odds of winning or losing for various projects they might launch or investments they might make. Some investments are far more risky than others. Knowledge of probability and statistics is critically important. Lottery tickets are a great example of bad odds. The math is discouraging. Each time we strike out on a venture, it pays to calculate the odds. In the case of the lottery ticket, they are printed on the back of the "play slip." But how many people notice or give the odds much thought?

This chart shows that you have one chance in 5,153,633 of winning a $1 million prize with your $2 ticket. One chance in five million! Those are not promising odds. The odds of winning at a casino are also discouraging, yet those odds do not keep gamblers away. Publicly available on sites such as PBS, there are lists showing the house advantages for table games and slot machines, but gamblers tend to ignore the odds and the statistics when they walk in the door. They may think about the odds of drawing a fourth ace when they are playing poker, and they may think about the odds of beating the dealer in blackjack when the dealer has a ten, but they tend to believe in luck. They have a sense that they will beat the odds, that the Goddess of Roulette will smile upon them and make the ball drop into their favorite numbers or favorite color with uncommon frequency. For serious gamblers, probability and statistics apply only when considering specific game strategies, but roulette players do not like acknowledging the house having a 5.26 percent advantage on all bets-- a significant edge. "If you're betting $100 an hour on roulette, you will, in the long run, lose an average of $5.26 an hour." Excerpt from James Walsh's 1996 book True Odds Merritt Publishing, 1996, Santa Monica, CA. There is, of course, a difference between what Costa is calling "taking responsible risks" and pure gambling. One especially powerful piece of fiction to help students understand risk, addiction and gambling is Dostoyevsky's The Gambler.

You can watch the trailer for the film made from this story here.

Planning a future by crossing your fingers?

No matter how efficacious a student may feel, entrance to an Ivy League college in the USA is not a lottery. No matter how lucky you may feel, if you have SAT scores below 600, you will probably not be going to Yale, Princeton, Harvard or Brown. There are life experiences that are open only to those who qualify. That being said, there may be ten candidates for each spot in Yale's freshman class who possess the right scores and numbers. Those who win a spot must demonstrate several other exceptionalities that set them apart from the other nine. It is not really a matter of luck. No one spins the "wheel of fortune." The university reviews the portfolios and the interviews until one of the ten stands out and the others fall by the wayside. The only luck involved might be the possibility that you are the only student applying who has written several piano concerti and your favorite university has chosen that talent as a top recruitment target. But along with that luck comes the smart strategy you pursued of meeting with a key professor in the music department when you did your campus visit. That professor will have mentioned you favorably to the admissions department and will have solidified your chances.

Those with the good scores must apply for a dozen universities in order to protect their chances. Or they may opt for early admission and hope their portfolio is strong enough to save them the trouble of "hedging their bets." The odds of winning a spot for this select group are better than winning the lottery. The most important strategy is presenting an impressive portfolio on top of their good scores and class rank. In some cases, this might include athletic or artistic excellence like the student composer mentioned above. Perhaps an alumni mother or father will improve the odds. But success largely depends upon decisions and actions taken during the four years leading up to application time. It is more a matter of hard work and talent than luck. Entrance to a great technical school or an outstanding school for artists is no more a matter of luck than it would be for an Ivy League university. While there may be a touch of luck involved, entrance mainly depends upon effort and accomplishments. Career choices may also involve a mixture of luck and merit. What are the odds that a cello player will perform in Carnegie Hall? What are the odds that a very talented ninth grade oil painter will become a nationally recognized, successful artist? It is harder to climb to the top in some professions than others. Parents of children with an artistic bent may warn their prodigies that, "It is hard to make a living as a painter or an artist." The odds are against any young singer, writer or painter. The odds might be better if they chose banking or law or medicine. Warned by their parents to avoid risky careers, many students will persevere and stick with their dreams, but many others will take a safer path. William Dietrich, writing in the Huffington Post, "The Writer's Odds of Success," says "Most successful authors have some combination of talent, persistence, and luck. The persistence stories are always encouraging. And daunting." Playing it safe? This article raises troubling issues about the relationship between success, luck and odds. Efficacy thrives on success. If our students plan their lives on the safe side, they may limit their goals to professions and careers with promising odds of success. They may steer clear of artistic careers, avoiding the stereotype of the "starving artist." What a shame for the society. While Dietrich thinks the persistence stories are encouraging, he only told stories of writers who persisted all the way to success. How about the tens of thousands of other writers who tasted almost none? We hope that students will not shy away from challenge. Resignation and fatalism are corrosive and debilitating. As stated earlier, it is more likely that students will act in an efficacious manner if they have firmly established strong habits of mind. Good teachers and schools will see to it. The development of efficacy should be a prime school goal.

|

||||||||||

Copyright Policy: Materials published in The Question Mark may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by email. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. FNO Press is applying for formal copyright registration for articles. |