Quality Teaching

A lifetime journey of exploration, practice and discovery

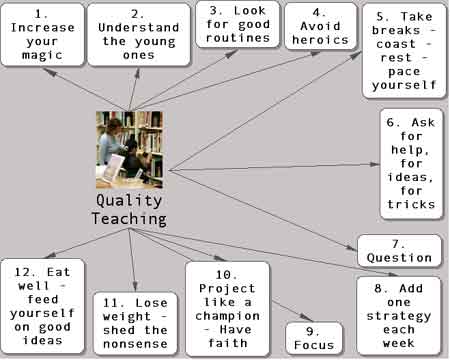

A Combination of Elements

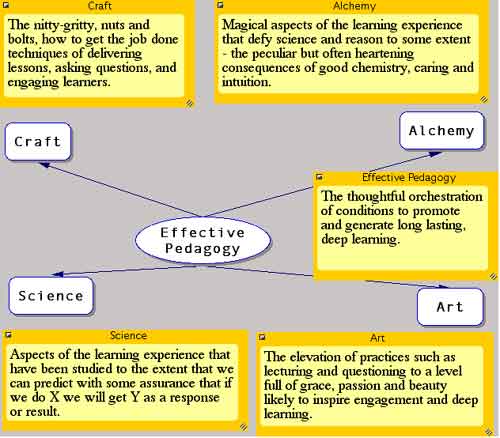

These days it is fashionable in many places to focus most of the attention on the science and craft of teaching while neglecting the art and the alchemy. Consideration of the magical aspects of good teaching is all too rare as serious scholars (and politicians) look the other way, showing little interest or faith in such aspects of effective practice. Sadly, a focus on just the scientific aspects of teaching or the so-called research-based aspects leads to an impoverished and inadequate view.

Managing classes with nothing more than the craft and the science of teaching starves students, depriving them of their right to a rich and inspiring educational experience. Such classrooms become wastelands - barren, lacking in soul and incapable of nurturing the young.

All four elements shown in the diagram below (craft, science, alchemy and art) are essential.

This call for balance gains acceptance from many classroom teachers who are likely to nod their heads knowingly. While they may prefer the word "magic" to the word "alchemy," teachers know that it takes more than science to spark learning in many students.

Effective teaching requires a dynamic orchestration of the four aspects listed above, orchestration that cannot be found in any book or score. The teacher must dart and weave, dance and charm.

Ho-hum-drum teaching leads to stagnation and disappointment.

Spirited teaching provokes, sparks and enlightens.

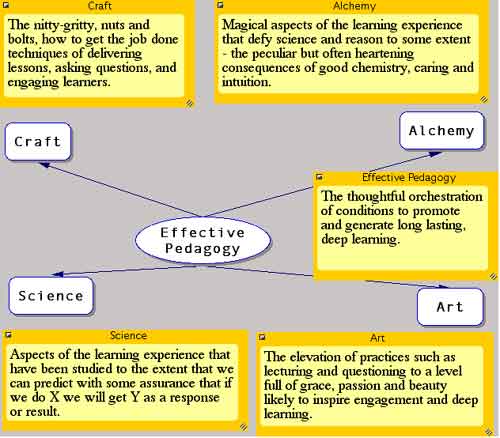

Providing the Conditions for Learning

Quality teaching is one aspect of a larger system, since there is a dynamic and complicated interplay between the social aspects of learning and the specific classroom experiences offered.

Some students enter school ready to learn most days. Others arrive distracted, hungry and unsettled. An effective teacher does whatever possible to create conditions that engage the full spectrum of students, but it is not always possible to counter the negative currents and influences contributed by a harsh or disturbing external culture.

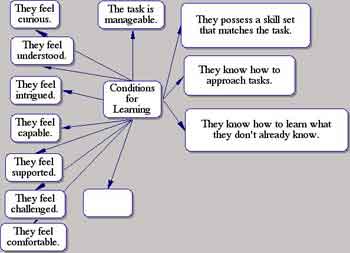

Young ones are most likely to learn when . . .

The list in the diagram above leaves out some critically important conditions that teachers are quick to add in an audience situation:

- They are well fed.

- They have had enough sleep.

- They feel safe.

- They know where they will be sleeping each night.

- They have a family that provides support and comfort.

Sadly, few policy makers on the national level seem willing to address these broader conditions when seeking improvement in schools. In countries where "quality teaching" is a current fashion, the teacher's work is portrayed as if one works within a vacuum free of these influences. Researchers seek the right packages, the right programs and the right teaching strategies to make impressive shifts in student performance, but that research is tragically flawed by its narrow focus on classroom interactions.

Looking for some kind of high pay-off and reliable approach, policy makers often commission what are called "best evidence syntheses" of research - trusting to the so-called science of teaching to inform policy.

Unfortunately, much of the policy that might emerge from such collections and efforts is flawed, in part because the collections are weak on science and tend to compound the imperfections of the thousands of original studies upon which they are based.

The Best Synthesis Trap

Each decade we witness heroic efforts to synthesize the research findings on "best practice" - a well intended but frustrating exercise in reform that has failed in the past to produce the major shifts promised.

These composite reform efforts fail basic tenets of logic. The act of scanning research reports for stories of success and student learning leads to a kind of patchwork quilt of practices each of which might have worked separately under certain conditions but were not proven to work in all conditions and were not actually proven to work as a group. Much of the research only proved association between isolated factors and variables rather than cause-and-effect.

The trouble with a synthesis is that it is a new form - an untested variant - a combination lacking a research base. It only appears to have a research base because it was extracted from research reports, but the synthesis is actually a new thing, a new approach lacking evidence to support its value.

The very act of combining a dozen abstract principles in a new model compounds the instructional challenge since the complexity of the model and the enormity of trying to implement it make the task daunting for classroom teachers.

When the authors of a synthesis propose action based upon their synthesis, they will claim their recommendations are research-based, but this is a very big stretch, as there never is research available on the effectiveness of the particular combination of recommendations being advanced and no research on how to translate the combination of grand theories and abstract principles into actual classroom practice.

The programs that result from this kind of research often arrive with exaggerated claims and promises that set in motion huge reform efforts that extend over decades and claim hundreds of millions of dollars, yet the results are often disappointing.

An Example: Teacher Expectations and Student Achievement

One such program that was all the rage in the 1980s was TESA (Teacher Expectations and Student Achievement), an approach that had shown some promise in Los Angeles County to narrow the achievement gap between males and females as well as minority students and white American students by training teachers to use fifteen classroom strategies.

TESA is still highly thought of by some educational leaders, as the state of North Carolina maintains a commitment to the TESA strategies at its Web site devoted to school improvement and the Los Angeles County Office of Education offers all kinds of workshops and products to support schools implementing the program.

- TESA TRAINING (TEACHER EXPECTATIONS & STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT)

Teachers' expectations strongly influence students' effort and performance. TESA training heightens teachers' awareness of their perceptions of classroom interaction with students as well as offers insight into how those perceptions actually affect their expectations of students.

- http://www.ncpublicschools.org/schoolimprovement/closingthegap/services/

What are the teacher strategies embedded in TESA and supported by a best evidence synthesis in the 1970s?

The strategies fall into three categories:

- Teacher management of 'response opportunities': equitable distribution of response opportunities, individual helping, response latency, delving and higher level questioning.

-

- Teacher feedback: affirmation of correct performance, praise, reasons for praise, listening and accepting feelings.

-

- Personal regard: proximity, courtesy, personal interest, touching and desisting.

-

- Sam Kerman, Phi Delta Kappan, v60 n10, p716-18, June 1979

- Definitions available at http://streamer.lacoe.edu/tesa/.

Strangely, once the program became popular in the 1980s, few educational researchers took the time to study whether it was achieving the results promised by the original authors. An ERIC search turns up only 16 articles that refer to TESA and only one of those articles is evaluative. That one evaluation raises serious questions:

- "Increasing Teacher Expectations for Student Achievement: An Evaluation" by Denise C. Gottfredson, Elizabeth Marciniak, Ann T. Birdseye, and Gary D. Gottfredson, CDS Report No. 25 (November 1995)

The 1995 Gottfredson evaluation was quite small and not very conclusive, hardly a ringing endorsement of the TESA program, but neither did the study provide a convincing basis for ceasing operations. ERIC abstract. The teaching strategies advocated by TESA retain face validity and continue to attract followers. The lack of conclusive evidence of positive impact upon student performance seems of little consequence as long as the program is claimed to be "research-based."

Ten years after the Gottfredson evaluation, TESA remains alive and well in many school districts, offered as an example of research-based effective practice even though the research base is thin, out-dated and inconclusive. The Los Angeles County Office of Education maintains a major commitment to TESA and publishes a full range of manuals and support materials for schools wishing to employ the strategies, but the site does not offer research evidence of improved student learning. TESA site.

Once a program like TESA gains acceptance, its worth is passed along like folk wisdom by dozens of other sites, some of which have conducted best evidence syntheses of their own.

It is difficult to argue against a program that stresses higher level thinking and balanced treatment of students, but it would be reassuring to have more evidence that the training leads to improvement.

The Challenge: Strategic Teaching in the Face of Novelty

Even though it may be the crux of improving performance, there is little research available touching on the decision-making and judgment required of teachers who seek to apply complex strategies and tactics to novel classroom situations.

The search for science, recipes and teacher proof packages cuts against a focus on teachers as inventors, thinkers and professionals who must juggle complexities.

Each day students walk into a classroom, teachers face novelty. Their training could not prepare them for the ever-shifting combination of personalities, moods and readiness levels that enters the classroom door at 10:10 AM on Tuesday morning. No lesson plan could possibly anticipate the true nature of the day's challenges. Teachers must adapt good intentions and plans rapidly as they diagnose, interpret and observe the reactions of their students.

Training models rarely equip teachers to manage these complexities. Techniques may be modelled and practiced extensively, but little is done to prepare teachers for the surprises that are basic to classroom life. Few teachers have ever been given courses in instructional design or strategic teaching.

Stumbling toward Competence

Little is written about teachers managing skill repertoires, yet it is this juggling and management that can create the best learning opportunities. Part magic, part art, part craft, effective classroom management employs the best of science blended judiciously with intuition and empathy.

Picture teachers acquiring thousands of strategies and tactics during a career. Once they possess a skill, they must hone their command of that skill or tactic, applying it to a complicated spectrum of students and situations. Mastery of a specific skill might take years. Training is just the beginning of a long journey.

Each day the teacher considers lesson objectives and strategies before students walk through the door. Once the students appear and the lesson begins, it is usually necessary to shift the lesson plan as the class proceeds and the teacher notes the reactions of various students. In many cases, the teacher must dig deep into the skill repertoire to find tactics that seem right for the situation that has developed. In some cases, the first new strategies will be successful, but it is a trial-and-error process.

Good teachers effectively "stumble toward competence" as they try out an array of strategies and tactics until they find the right ones. Experience helps to inform their choice of strategies, but novelty stands in the way of any teacher being able to coast along banking on previous experience.

Match-making

Effective teachers engage in daily match-making, creating conditions to promote learning and connecting tasks with students, giving them what they need to be successful while nurturing the process and minimizing obstacles. The best teachers customize lessons so that each student is afforded opportunities that match needs, interests, preferences and skill levels.

A Discovery Process

A Discovery Process

If at first you don't succeed . . .

Much of what translates into effective classroom practice must be discovered rather than learned formally in training sessions, yet the discovery process is rarely studied, mentioned or valued.

We are reminded of the classic story of Robert Bruce watching a spider spinning a web, failing repeatedly but persisting until successful. Strong teachers understand that the process of developing effectiveness requires much spinning, much webbing and great persistence in the face of challenge.

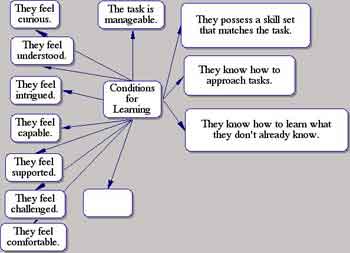

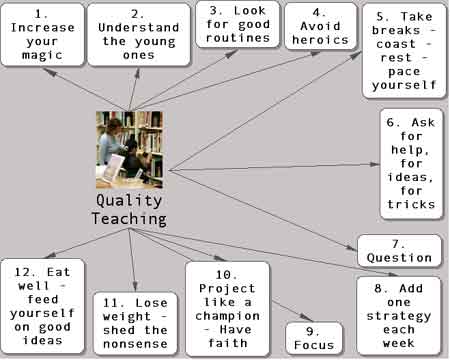

Consistent with the blend of magic, art, craft and science mentioned above, this article offers a dozen strategies for teachers to consider as they plan their personal journeys of discovery and growth.

You can click on a strategy in the diagram below to read what is suggested for each.

- Increase your magic

- Understand the young ones

- Look for good routines

- Avoid heroics

- Take breaks - coast - rest - pace yourself

- Ask for help, for ideas, for tricks

- Question

- Add one strategy each week

- Focus

- Project like a champion - Have faith

- Lose weight - shed the nonsense

- Eat well - feed yourself on good ideas

1. Increase your magic

The success of a teacher depends to some extent upon magic and alchemy - the ability to do some or all of the following:

- Spark learning

- Cast spells

- Awaken thirst

- Captivate

- Charm

- Delight

- Disarm

- Deliver (In the sense of setting free.)

And yet, there is little in the formal preparation of teachers that would equip them to succeed with this aspect of quality teaching. It is rare to find a teacher who was offered a course in presenting winning, dramatic, captivating lectures or a course in capturing the hearts and minds of students. This dimension is pretty much ignored and neglected by formal pre-service programs, but it is often a deciding factor in how students respond to classroom challenges and teachers.

How does a teacher increase magic? In most respects, the task resists training and methodology. There is always a danger of courses offering to teach virtual sincerity - charm school for teachers!

Actually, the learning process probably starts on a very individual and personal level as a teacher acknowledges that human chemistry and magic are prime elements in learning. Once the teacher embraces that notion, the search begins. Is charisma and chemistry an accident of birth? Can they be developed, enhanced and amplified?

To some extent, magic in the classroom is a matter of mastering tricks of the teaching trade - much like card tricks and sleight of hand. But those tricks and tactics are a subset of a larger and probably more important range of magical effects, those concerned with the human chemistry and relationships of the classroom. These should not be a result of trickery and sleight of hand. In many cases, the warmth we see in a particular classroom was probably kindled over several months as the teacher greeted the students each day, showed interest in their lives outside the classroom, discovered their personal concerns and passions and demonstrated an appreciation and empathy that seemed genuine. Chances are this foundation was then amplified on a class by class basis by the teacher building a bridge for the students between their concerns and the content at hand, bringing the history or the math to life in vivid terms.

We can learn some of this by watching and reading, but much of the learning requires action, effort and experimentation. Deep magical connections are rooted in primal human communications such as eye contact and emotional vulnerability.

If someone is bad at eye contact, how do they get better?

When the adult teacher is a closed and guarded person, magic is a stretch. The more controlling, distant and authoritarian the teacher, the less likely magic will occur. The whole challenge of increasing magic is a bit outside the reach of policy as it depends fundamentally upon human dynamics and choices that are more individual than institutional.

We can increase magic in schools by hiring more magical teachers and we can increase magic by providing support for individual teachers to work on this aspect of their profession, but we cannot easily legislate these changes.

Each teacher makes a personal choice. When making magic a priority, a teacher opts for a career that may bring amazing psychic rewards. These teachers find that teaching is about releasing human potential and transformation. By tapping into the spiritual dimension of learning, these teachers open themselves to the greatest possible rewards, but there is a dark side to such openness, since not all efforts succeed and not all students respect the vulnerability.

2. Understand the young ones

Effective teachers work very hard to understand who the students really are, to uncover their hopes, fears, wishes, dreams and trials in order to get to the heart of the matter. By personalizing the classroom and the search for meaning, they win loyalty, commitment, interest and effort.

We know that it is difficult to develop intimate relationships when we load teachers with 150 adolescents per day, yet few governments are willing to tackle the class size issue because of its financial implications.

3. Look for good routines

Critics often make it seem that schools are plagued by dull routines and dull teachers, but good routines are an essential aspect of surviving the pressures and chaos that characterize life in schools. We should honor the value of good routines and support those teachers who see the value in refreshing , enhancing and augmenting their routines.

Effective teachers acquire thousands of tricks of the trade - classroom moves and tactics - strategies to induce learning and achieve good results. This vast repertoire of strategies provides a rich and varied choice of interventions so that the teacher can make the good matches mentioned earlier between learners and learning opportunities.

The process of adding to the repertoire should go on throughout one's entire career, as a good teacher keeps looking for ways to enhance effectiveness and continues to seek information about new challenges such as the arrival of a new group of immigrants.

It is not enough to read about a new routine or see it demonstrated in a workshop. The teacher must adapt it, practice it, adapt it some more and manage to fit it into the life of the classroom in a way that is comfortable and consistent with other routines. The process is akin to honing or whetting a knife blade until perfectly sharp.

4. Avoid heroics

At times the strategies advanced in this article may appear contradictory or in conflict with each other, but that is because teaching requires an appreciation of paradox and a tolerance for ambiguity. Thus we see that heroics can get a teacher in trouble, yet later we argue that effective teachers project like champions. How does an individual reconcile these two seemingly contrary recommendations? The answer of course, is a matter of judgment and discretion, of balance and emphasis.

When the teacher goes out on a limb and becomes overextended, the energy required to reach students and achieve results becomes depleted and the level of stress is so high that it easy for the teacher to slip into patterns of behavior that are actually counter-productive.

Modulation is key to success.

5. Take breaks

Teaching is a bit like running a marathon. Pacing is essential. In order to replenish, recover and restore the reserves necessary to fuel passionate teaching, teachers must learn to coast, rest and take advantage of plateaus.

Sadly, coasting has been given a bad name and is seen as slacking by many outside the profession. If only we ran our schools like buzzing factory floors with rewards for frenzied activity, the argument goes . . .

As with many of the so-called helping profession, burnout is a risk for teachers who run too fast, give too much and forget to take care of their own needs. Managing the energy flow in and out of the psychic system is basic to survival, yet little is done to prepare young teachers for this aspect of career management.

6. Ask for help, for ideas, for tricks

How strange that some reformers push schools to become more competitive. Growth and change are more likely to thrive in more collaborative cultures. When teachers gather in mutually supportive communities of practice, trading good techniques, exchanging stories of change and experimenting together, they stand a good chance of advancing their skill levels and persisting through difficult trials. In contrast, the isolation that too often characterizes school cultures undermines performance and growth.

In some schools, asking for help is seen as weakness.

In some schools, sharing successful strategies is seen as endangering merit pay rewarded for outstanding scores.

Quality teaching is demanding and exhausting, often frustrating and painful. Fellowship can play a major role in validating one's worth as a teacher during the toughest moments but it can do more than that. Just as partners and ropes permit rock climbers to scale seemingly impossible peaks, team support can give teachers the lift they need to reach optimal levels of performance.

7. Question

When we stop questioning, we stop learning and growing.

At the end of a day of teaching, many teachers reflect on the hours that have passed, rewinding the tape to consider what worked, what inspired, what stumbled and what they might change in the future. This reflective process is central to the growth process, and questions are the tools that enable the following to thrive:

- Wondering

- Considering

- Predicting

- Challenging

- Testing

- Probing

- Stretching

- Inventing

Ideally, the questioning teacher becomes capable of reinvention and is never stuck for long in ruts or slumps.

8. Add one strategy each week

From theory into practice

It takes lots of time to understand, to test, to adjust and to adapt each new strategy until it fits comfortably into daily practice. If a teacher sets the goal of adding one new strategy a week, it may prove too ambitious, for the process of skill acquisition may extend over several weeks for each new strategy, but the conscious personal commitment to building one's repertoire is central to the model of quality teaching advanced by this article.

Quality teaching amounts to a lifetime journey of exploration, practice and discovery.

9. Focus

Quality is enhanced by digging down deeply into particular aspects of performance rather than spreading oneself thin and emerging as dilettante, dabbler and piddler. A teacher might Identify one major category to enhance such as questioning, for example, and could easily spend an entire year just modifying lessons using strategies such as the Question Press. (FNO article, February-March 2004)

In a similar vein, a teacher with a load of 150 students each day might select a half dozen especially worthy students for special effort during a period of days and weeks. There may be several students going through special difficulties. Others might need a nudge. Some may be on the verge of a break through. The teacher invests heavily and strategically in a half dozen or more students to set in motion good works of various kinds.

If we concentrate on deep and major effects, teachers are more likely to make a difference.

10. Project like a champion

In contrast with the earlier section warning against heroics, this section urges the teacher to communicate faith, encouraging young ones by example and modeling. The job of the teacher is, to some extent, to defy the odds and unleash human potential that might have been, for one reason or another, been blocked.

- Have faith

- Encourage

- Model

- Inspire

- Challenge

- Reach

- Extend

- Defy

11. Lose weight - shed the nonsense

As the teacher adopts new routines and expands the teaching repertoire, the acquisition of new techniques should be accompanied by a shedding and pruning process as the teacher identifies the rituals, practices, programs, strategies and resources that have failed.

The goal is to eliminate all but the worthy, the promising and the effective.

12. Eat well

Another paradox! How can we talk about eating well and losing weight in the same breath?

It is all about avoiding empty calories and feasting on ideas that are lean and nurturing at the same time.

- Feed yourself on good ideas.

- Establish and maintain a robust flow of promising concepts, strategies and techniques.

- Go far afield in search of novelty.

- Balance novelty with bread and butter basics.

The Question Mark

The Question Mark

A Discovery Process

A Discovery Process