Long before Katrina struck, studies had warned that the levees might collapse and the city would be flooded just as it happened this past week.

Confronted by such dire warnings, planners are expected to do at least two things:

- Invest in preventive strategies like building stronger levees.

- Create disaster plans to take care of a population and a city that is drowning.

A disaster plan that stops with the sending of flood victims to a gathering place is tragically flawed and narrow minded because we could all anticipate that these victims will need basic survival resources once they have gathered.

- Food, water and medical attention

- Security

- Bedding, clothes and sanitation

- Hope

- An exit strategy

- Temporary substitute housing

- Emergency funds

Once collected in the Super Dome or the Convention Center, the thousands of souls who followed instructions were left without any of the basics that should have been provided by the local government, the state government and the federal government.

This is not rocket science. It is Disaster Planning 101. All three levels flunked.

Preparedness in an Uncertain Age

Few school programs have stressed the kind of divergent thinking required to think the unthinkable, yet all societies are likely to face unthinkable challenges during this age of uncertainty. If we raise young people to rely upon the tried and true, last year's standard operating procedures and conventional wisdom, unusual events will overwhelm us and paralyze us when these young ones later become leaders of various kinds.

But thinking the unthinkable is important for regular citizens as well as leaders, as families must cope with major shifts in employment opportunities, social conditions and calamities of various kinds.

This kind of thinking is a basic skill that we should expect all to learn. This kind of thinking is a critical component of decision-making and problem-solving. Without such a capacity, individuals and leaders will be hamstrung by surprises.

"This storm was bigger than anything we've ever seen before."

Excuses ring hollow when leaders fail to rise to their responsibilities in ways that end up causing unnecessary deaths and aggravate already catastrophic events.

When Surprise is No Longer Surprising

If students must confront surprise every day of their life, surprise is no longer surprising and young ones will learn to take surprise in stride. They become resourceful and resilient. They do not whimper, whine, make excuses and duck responsibility. They take hold of each new challenge with a sense of enthusiasm and confidence.

Few schools offer such a diet of daily challenge. In many schools, learning is about mastering conventional wisdom. Schools often focus on the transmission of knowledge and culture, making sure that young ones have mastered the wisdom of the ages and the sages. Schools sometimes stress the mastery of routines to the exclusion of considering surprise.

Fortunately, we see some governments and educational ministries pointing out the importance of such learning. In one section of the report outlining skills expected by the New Zealand Curriculum, for example, there is a strong list of decision-making skills:

- Students will:

• think critically, creatively, reflectively, and logically;

• exercise imagination, initiative, and flexibility;

• identify, describe, and redefine a problem;

• analyse problems from a variety of different perspectives;

• make connections and establish relationships;

• inquire and research, and explore, generate, and develop ideas;

• try out innovative and original ideas;

• design and make;

• test ideas and solutions, and make decisions on the basis of experience

and supporting evidence;

• evaluate processes and solutions.

The New Zealand Curriculum specifies eight groupings of essential skills: http://www.tki.org.nz/r/governance/nzcf/ess_skills_e.php#info

Proclaiming such goals is one thing, but the actual accomplishment is quite a different matter. To develop skills like those listed above, young ones must spend a good portion of their school experience working through problems. Schools that limit the young to absorbing the lessons of the past and mastering the tried and true will fail to meet the challenge.

The Value of Case Studies, Simulations and Role-Playing

One effective method of developing decision-making and problem-solving skills is to engage students as if they were teams of actual decision makers facing a crisis or challenge of some kind.

- Example One:

- "Imagine you are a planning commission charged by the mayor and city council to come up with a disaster plan to safeguard the citizens of our town on the event of a crisis (hurricane, cyclone, earthquake, volcanic eruption or terrorist attack). What plan of action would you recommend?"

-

- Example Two:

- "Imagine you were running the convict prisons in Tasmania during the first twenty years of that settlement. What changes would you recommend in the way they were operated and the way the convicts were treated?"

-

- Example Three:

- "Imagine you were running detention camps for illegal aliens in the USA or Australia today. What changes would you recommend in the way they are operated and the way the detainees are being treated?"

There is a substantial body of research outlining ways to use these methods with students.

Asking the (Apparently) Irrelevant Question

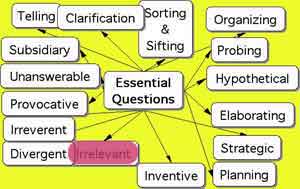

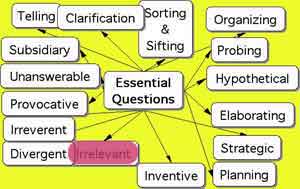

The irrelevant question is a powerful member of the Questioning Toolkit . While its power is counter-intuitive and its practice is rare, it is a keystone in the thought process we are considering as thinking the unthinkable.

One must learn to escape from the limitations of conventional wisdom and thinking by ranging farther afield. In fact, this kind of exploration requires dramatic excursions into unfamiliar terrain.

Exploring the Dark Side - the Negative Space of Life

Artists frequently employ the concept of negative spaces to capture the shape of spaces surrounding an object.

The same concept works well to identify the missing parts of a mental puzzle.

We try to extend our search beyond the boundaries of what we already know. We aim our searchlight into the shadows and the dark places.

We cast light into corners, under bushes, into closets, and through locked doors and barriers.

When we see governmental failures on the scale of FEMA's limp response to Katrina, it is because the bureaucrats have failed to consider the worst that might happen and have neglected to fashion plans to deal with such horrific conditions.

For a thorough explanation of strategies to teach students this type of questioning and thinking, note the article, "The Seemingly Irrelevant Question" in the September 2004 issue of the Question Mark. Click here.

The article explores six strategies:

- Strategy One - The Jigsaw Puzzle, Juxtaposition, and Worst Case Scenarios

- Strategy Two - Reversal

- Strategy Three - Grab the Tail

- Strategy Four - Purposeful Wandering - Learning to Get Lost!

- Strategy Five - Theater of the Absurd and Beyond the Pale

- Strategy Six - Taking Soundings and Mapping the Unknown

The Question Mark

The Question Mark