|

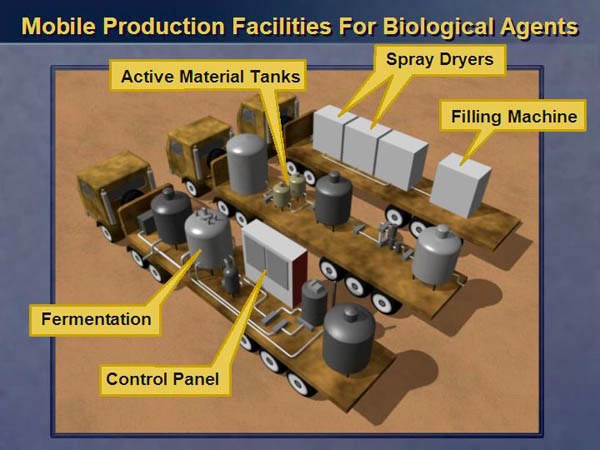

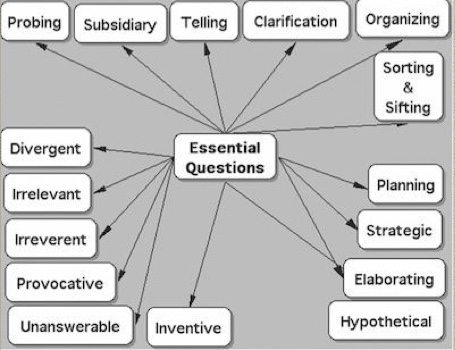

Note: The Research Cycle shown above was developed in 1995 to meet the need for a more robust approach to school research that would involve teams of student working on essential questions.

A brief version appeared in Multimedia Schools in June of 1995 and a much fuller description, was made available in a six article series in Technology Connection.

In November of 1996, a revised, short version appeared as part of an article in Educational Leadership.

© iStock.com

Sometimes people launch their research before they know enough to pose the right questions. They don't know what they don't know - a dangerous form of blindness.

They often have preconceptions and bias that may block them from finding the truth. Instead of searching with an open mind, they go looking to confirm what they believed when they started. They ignore evidence that contradicts their initial bias.

The Research Cycle was designed to protect against this kind of research.

© iStock.com

The path of least resistance and least trouble is a mental rut already made. It requires troublesome work to undertake the alternation of old beliefs. Self-conceit often regards it as a sign of weakness to admit that a belief to which we have once committed ourselves is wrong. We get so identified with an idea that it is literally a “pet” notion and we rise to its defense and stop our eyes and ears to anything different.

John Dewey

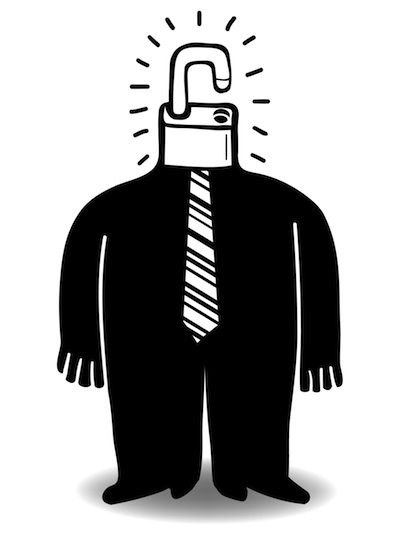

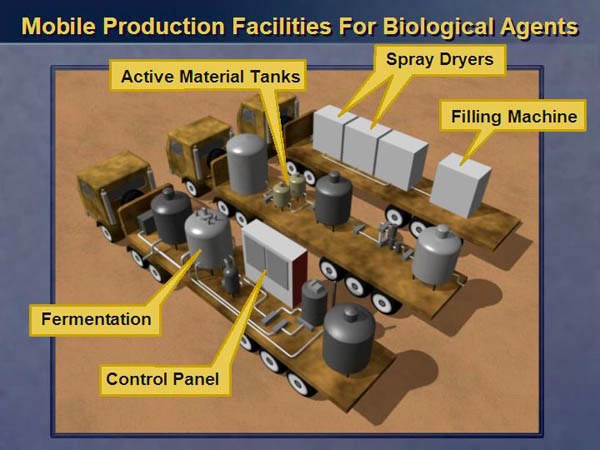

The classic example is the Bush administration's conviction that Saddam Hussein was hiding weapons of mass destruction. Believing this to be true despite a lack of evidence, they began looking for those facts that might support their preconception.

Secretary of State Colin Powell stood before the United Nations to show photographs that he claimed proved their accusations. Soon after, the United States launched an attack on Iraq that led to much death and destruction, but once they invaded the country, they never found any weapons of mass destruction.

From the Powell UN Iraq presentation, alleged Mobile Production Facilities

The importance of a truly open mind

© iStock.com

The Research Cycle was designed to help researchers, both adult and student, to tackle challenging questions and issues in a thorough manner. It guards against simplistic thinking and mere scooping. It requires repeated and sustained questioning. While the Internet and Google now make it easy to find answers, these are not always reliable or trustworthy. The Research Cycle offers an approach that encourages the thinker to build answers rather than simply cutting and pasting the ideas of others.

Because many people and many students don't know what they don't know when they launch their research, they tend to plan their exploration limited by preconceptions.

As an example of this phenomenon, I once had a telephone conversation with a high school student in Bellingham, Washington, where I was the Director of Libraries, Media and Technology, who asked me questions for half an hour, at the end of which she thanked me for my time but said she could not use what I had told her.

I was disappointed, of course, and asked her what was wrong.

She explained that she had a thesis -- that we would not need libraries or librarians because of the Internet -- and my comments had undermined rather than supported that thesis.

I suggested she might modify her thesis based on new information, but she claimed they were not supposed to do that.

This was the antithesis of true research.

The most powerful premise guiding the Research Cycle is the importance of mucking around and learning about the challenge at hand with an open mind so as to discover issues and questions not evident to those who either know very little about the challenge or mistakenly think they know more than they really do.

This makes the first stage -- Questioning -- something that must be repeated over and over. In fact, while the model outlines stages that seem to flow from one to another, they sometimes overlap and occur simultaneously. Thus, questioning may continue throughout as the researcher must revise strategies whenever new information demands a shift.

It makes little sense to form a thesis prior to substantial investigation, as a premature thesis is likely to limit the subsequent fact-finding as it did in the case of the high school girl mentioned above. Instead of conducting a search for truth, it becomes the defense of a position. It is wise to hold off forming a thesis statement until after completing at least one round of the Research Cycle. Even then, the thesis statement should be viewed as a tentative hypothesis rather than a firm position.

© iStock.com

Questioning

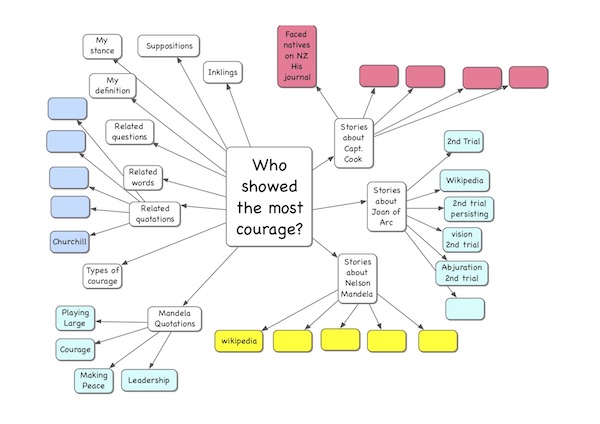

If struggling with a truly challenging question, either an essential question or a question of import, the researcher must first browse related information to learn enough to suggest pertinent subsidiary questions like those shown in the diagram below. This brainstorming is outlined in detail in the article, "The Questioning Toolkit - Revised."

A fifth grade example

Studying exploration, a fifth grade class is asked by their teacher to pick three ship captains and then decide with which one they would have chosen to sail. One student picks James Cook, George Vancouver and William Bligh.

In contrast with topical research which would allow a student to scoop up and regurgitate heaps of informaiton about a single captain, this research task puts the students at the top of Bloom's Taxonomy - requiring the skill of evaluation. They must decide upon criteria specifying the qualities of a good captain and then gather data to compare and contrast their three men.

Who shall it be?

By organizing essential and subsidiary questions prior to conducting research, students will be able to focus subsequent energy on pertinent information instead of gathering huge piles of information, much of which will contribute very little to the choice of a captain.

First the students must determine the traits of a good captain and surround the central question with those concepts. For example:

Good listener?

Courageous?

Resourceful?

Inspiring?

Clever?

Honest?

Fair?

Commanding?

Navigation skill?

For each trait, the students must list telling questions that would develop sufficient evidence to support making an informed judgment.

For example, to decide which captain had the most navigational skill, the students would have to find answers to questions like the following:

Did he know how to use all the best instruments of his time?

Did he keep a careful log?

Did he usually know where they were?

Did he ever get lost?

Did he seem to know what he was doing?

Did his ships have to wander around very much?

Did he stay clear of known hazards?

Did he know how to make the best of prevailing winds?

Did he know how to maneuver during a sea battle?

Did he have mates that could help him when he needed it?

Did he know when to ask for directions?

Planning

During this stage the researcher figures out where to look and how to store pertinent information so it will guide thinking about the questions at hand.

Where will we find pertinent and reliable information other than Google? It is one of the many reasons we still need librarians, as they are trained to help us find trustworthy information without relying too much on Google.

Many turn too quickly to sources like Wikipedia and Google. While these may suffice when comparing hotels for a holiday, other sources may prove more valuable when researching something like figures from history or complex scientific issues. Much of the content on the Internet has been developed by amateurs or those with a distorted point of view and ax to grind.

Online biogrpahies, for example, rarerly provide the depth and accuracy of a book like The Trial of the Cannibal Dog: The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook’s Encounters in the South Seas a carefully researched account written by Anne Salmond - Distinguished Professor of Maori Studies at the University of Auckland and a Pro-Vice Chancellor of the University. |

|

Some of the most reliable information will be found in printed books or their online equivalent. Many schools also subscribe to online periodical services that are not available to read when searching with Google. Librarians can also help students and adult researchers mine the valuable resources to be found on what is know as the "Deep Internet" -- more sources not available through a Google search.

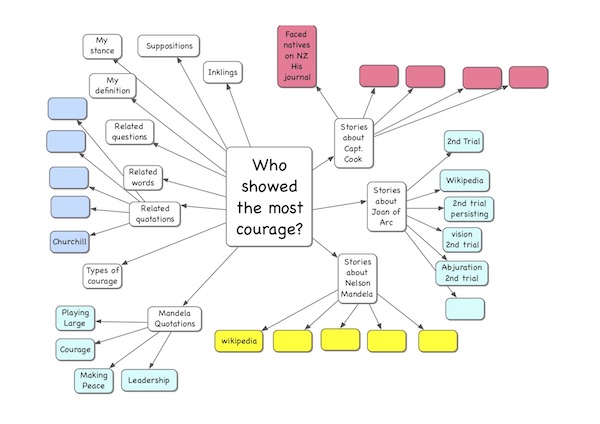

In addition to planning how to find trustworthy information, another goal of this step is to create a storage system that will protect students from accumulating huge mountains of information pasted together in one long scrolling mishmash. Retrieval from such a hodgepodge can be a daunting task. Mind mapping software supports thoughtful storage of findings close to the pertinent questions. While word processing documents or a database file may also be used to organize findings, these are relatively clumsy.

The diagram below shows how mind-mapping can organize findings on a complex question comparing Nelson Mandela and James Cook with Joan of Arc.

We hope to dissuade students from wholesale cutting and pasting. By planning ahead, they will have an information storage system to support concept-based retrieval, synthesis, and analysis. They will gather only information that casts light on the questions they have posed.

Organizing gathering around key ideas, categories and questions increases the likelihood that this activity will provoke and inspire thought while it is happening. Under older models, student(s) gathered first and tended to think (if at all) later. We hope to maintain the tension of good questions, cognitive dissonance and energy during the gathering stages.

Gathering

If the planning has been thoughtful and productive, the student proceeds to satisfying information sites swiftly and efficiently, gathering only information that is relevant and useful. Otherwise, he or she might wander for many hours, scooping up hundreds of files that would later prove frustrating and valueless.

It is critically important that findings are structured as they are gathered. Putting this task off until later is very dangerous when coping with infoglut. It is also crucial that students only use the Internet when likely to provide the best information. In many cases, books and other information sources will prove more efficient and more useful.

Sorting and Sifting

The more complex the research question, the more important the sorting and sifting providing the data to support the next stage - synthesis. Much selecting and sorting should occur during the previous stage - gathering - but now the researcher moves toward even more systematic scanning and organizing of data to set aside and organize those nuggets most likely to contribute to insight. The researcher sorts and sifts the information much as a fishing boat must cull the harvest brought to the surface in a net.

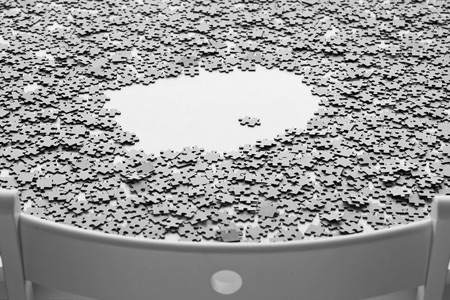

© iStock.com

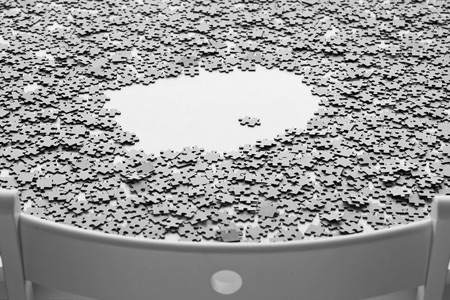

Synthesizing

In a process akin to jigsaw puzzling, the student(s) arrange and rearrange the information fragments until patterns and some kind of picture begin to emerge. Synthesis is fueled by the tension of a powerful research question. This stage is fully outlined in many articles on this Web site and at http://fno.org:

Evaluating

At this point, the researcher considers what is known so far and asks if more research is needed before proceeding to the reporting stage. In the case of complex and demanding research questions, students must usually complete several repetitions of the Cycle since they usually do not know what they don't know when they first plan their research.

Their first efforts usually greatly expand the number of questions posed at the outset, requiring new gathering and synthesis.

The timing of the reporting and sharing of insights is determined by the quality of the "information harvest" and the resulting synthesis. During this evaluation stage, the researcher decides if she or he is ready to formulate a position and share it with others.

Reporting

Once the research has cast enough light on the main question or challenge, it is time to consider how best to share findings with the appropriate audience. We have seen far too much PowerPointlessness in the past two decades and the challenge of reporting and persuading deserves an additional article outlining choices and setting standards to avoid the glib while delivering a message that is both powerful and persuasive.

|