The Question is the Answer

by Jamie McKenzie (about author)

Photo © iStock.com

Student questioning is at the heart of making meaning and grasping difficult concepts, yet in many classrooms, the focus is upon teacher questioning with those questions often delivered rapid fire with "wait time" of less than 2 seconds.1

Such teaching generally will focus on memorization and lower order thinking rather than the kinds of challenging thought required for success on test items like those developed for the Common Core.

In this article we will explore the possibilities of blending both teacher and student questioning into the same activity with the goal of asking students to construct answers to very difficult questions generated sometimes by the teacher and sometimes by the students.

To illustrate this process, we will use one example from literature — The Great Gatsby — and one from history — Captain Matthew Flinders' capture and imprisonment by the French on Mauritius.

Try one question instead of many!

Instead of the teacher firing off dozens of questions to see whether the students read and understood the material assigned the night before, it makes better sense to identify one "question of import" and build the entire class around that question.

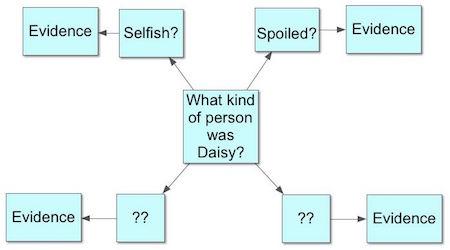

With literature, one might easily devote a class to issues of character. In the case of The Great Gatsby, for example, all of the following would serve quite well:

- What kind of person was Daisy Buchanan?

- What kind of person was Tom Buchanan?

- What kind of person was Jordan Baker?

- What kind of person was Nick Carraway?

- What kind of person was Myrtle Wilson?

- What kind of person was George Wilson?

- What kind of person was Meyer Wolfshiem?

To pursue one of these in depth, the teacher will require each student to spend at least 15 minutes rereading the text in search of evidence to support characterization and will expect students to begin constructing an answer either on paper or on their laptops.

"I am looking for you to suggest 4-5 adjectives to describe Daisy's character, and I will be expecting at least one or two citations from the text to support each of your adjectives."

Image courtesy of Bev Johnson, a RISD student. behance.net/bevsi

|

As students begin building their answers and looking for evidence, the teacher circulates and monitors their work. This is an approach that was called "writing for thinking" back in the 1980s when I picked it up at a workshop. The key element is the requirement that all students wrestle with building an answer and are given plenty of time to do so. Public display of work is also crucial so the teacher can make sure everyone is doing the thinking and may intervene to support and redirect the work of those who are experiencing difficulty and those worthy of encouragement. |

Examples of possible student questions

- What did Daisy do that showed character?

- What did Daisy say that showed character?

- What adjective best captures the character she showed?

- Were there other times she acted in this same way that would strengthen the case?

- Did she sometimes act in the opposite way, so it is not a constant characteristic?

- Does she change during the book?

- Can people ever change these basic character traits?

- Does Daisy try to hide her true character?

- Is Daisy deceitful?

- Do others like Gatsby see the "real Daisy?"

- Is there a "real Daisy?"

- If people are like onions, with layers of personality, which layers does Daisy share?

- What drives Daisy?

- When she speaks of giving birth to a girl, what does that tell you about her?

- Is Daisy a tragic figure? or a pathetic figure?

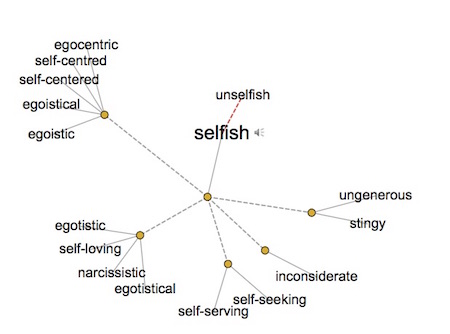

While searching for adjectives, the teacher should encourage students to consult one of these online thesauruses:

Is "selfish" the right word?

The above diagram was generated at the VisualThesaurus.com and used here with permission for ThinkMap, Inc.

We expect students to hone their word choices to select the best words to capture the character of Daisy or others. There is a big difference between "narcissistic" and "inconsiderate."

This approach contrasts dramatically with the "off the top of your head" classroom strategy during which the teacher throws out the character question and calls on a half dozen "rapid hands" who typically dominate class discussions.

Photo © iStock.com

Even if the teacher presses each contributor to back up claims with evidence from the story, the class will be skimming along the surface, and many of the students may not be seriously considering the question since they are accustomed to letting the "rapid hands" carry the day and do their thinking for them.

An Example from History

Photo © J.McKenzie

Statue of Flinders in Melbourne

|

This publication has always attempted to illustrate effective strategies using curriculum material from inside and outside the USA.

Matthew Flinders was a fascinating character who was the first European to successfully circumnavigate Australia and prove that it is an island continent.

On the way home from Australia to Britain during his last voyage, he was captured and imprisoned by the French on the island of Mauritius.

Like many important figures in history, Matthew made some "errors of judgment" that led to his imprisonment. The learning strategy outlined here would work well for Benedict Arnold, Queen Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603)

or Lin Zexu (whose forceful opposition to the opium trade was a primary catalyst for the First Opium War of 1839–42.) |

Where did Flinders go wrong?

The teacher asks the class to explore this question of import and propose with 20-20 hindsight what he might have done differently in order to avoid imprisonment.

Sailing home to Britain, Flinder's ship began to fail and sink, leaking badly, so he was forced to sail into the harbor at Mauritius ("Île-de-France") even though Britain was at war with the French. Thinking his scientific passport would protect him, Matthew soon found himself in serious trouble. He was imprisoned from 17th December 1803 to June 1810.

"Where did Flinders go wrong?"

The teacher supplies the question of import, but the students are again, like above, expected to develop and defend answers. Given the benefit of 20-20 hindsight, they must identify Flinders' missteps and suggest how he might have handled his arrival in Île-de-France more skillfully and more diplomatically.

The activity may extend over several class periods as students will scour the historical documents to figure out what went wrong and how Flinders may have acted badly. Given his status as a national hero, some of his missteps have been downplayed and misrepresented by loyal biographers. Students will find conflicting views of his behavior. They must weigh the views of apologists against those of critics, and they must beware of sources like Wikipedia that routinely minimize his failings as his fans edit entries to play down his failings.

|

"Where did Flinders go wrong?" is a question about strategy. Students must look at a series of actions and decisions he made starting with his acceptance of a leaking ship (the schooner Cumberland) to sail homeward and his acceptance of a trunk of documents that violated the terms of his scientific passport. Once he sailed, they must look at his decision to point his leaking ship into the harbor in Mauritius and his subsequent feud with the French governor, General De Caen. Invited to dinner, he refused, angered by his interrogation that he viewed an insult to a gentleman officer.

Photo © J. McKenzie

Statue of Flinders in Sydney |

Students must look at Flinders' actions and choices and ask which ones were ill-considered. They must build a family of questions like those mentioned above for Gatsby. And then they must suggest how he might have changed history by acting differently.

- Where did Flinders go wrong?

- What are the bad decisions he made?

- Which decisions did he have no choice about?

- Which decisions could he have changed?

- When is 20-20 hindsight stupid?

- Were Flinders' bad decisions a result of his character?

- Can anyone escape their character?

- Did Flinders regret his behavior?

- What did he write to his wife and friends about his imprisonment?

- How did his wife and friends react to his letters?

- Are there cases when honor is more important than survival?

- Are some people prisoners of a code of conduct that fits their station in life?

- What price liberty?

In both of these classroom examples, the teacher opened the inquiry by posing a question of import, but most of the questioning is done by the students seeking answers to those questions of import. In future lessons, the teacher may ask the students to propose the questions of import.

Photo ©iStock.com

Equipping Students with a Questioning Toolkit

In many previous articles I have argued that schools must equip students with a questioning toolkit that they will apply to inquiry tasks like those outlined above.

Effective questioning involves strategic mixing and matching of question types in combinations much as a boxer will mix and match punches. The boxer approaches an opponent with a flurry of punches coming from different angles, a mixture of jabs, uppercuts and other blows landing in quick succession.

In 1997 I published an article "The Question is the Answer: Creating Research Programs for an Age of Information." Twenty years later, this article remains timely and apt for schools that wish to make student questioning a priority.

Footnotes